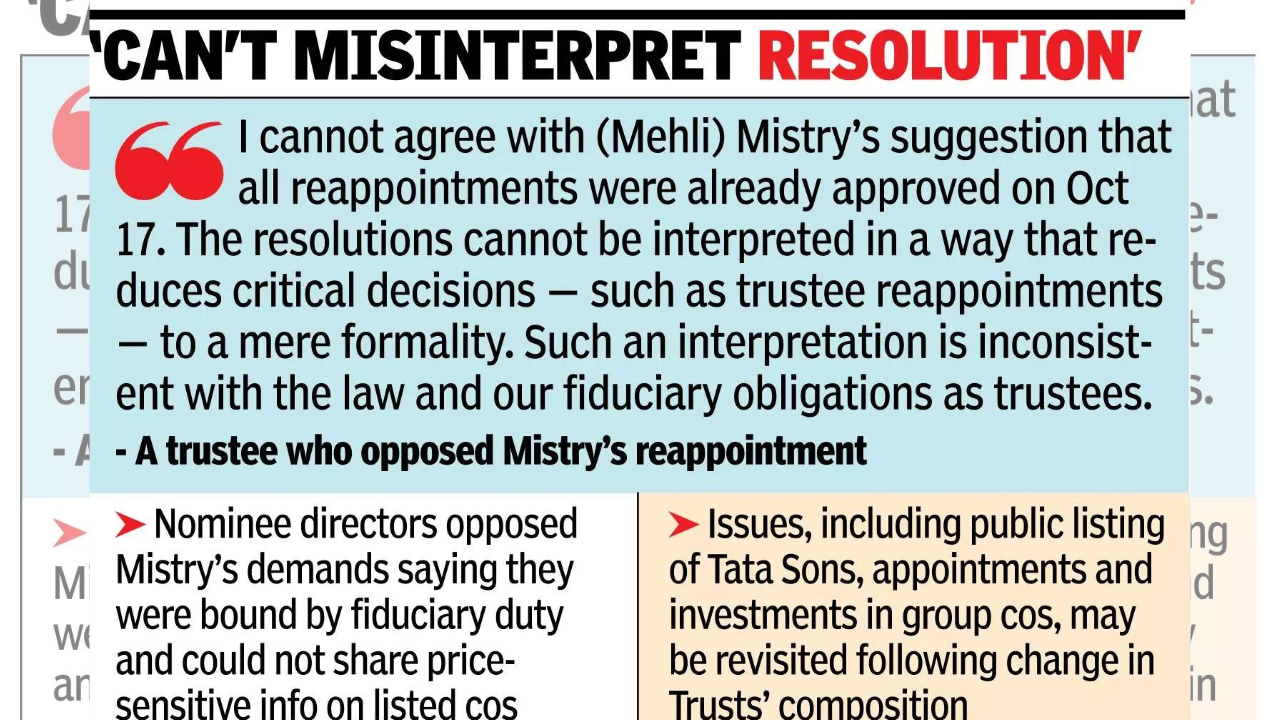

MUMBAI: The departure of Mehli Mistry from boards of Tata Trusts not only cements chairman Noel Tata’s position within the public charities but also strengthens his influence over the $180-bn Tata Group. It gives Noel greater control over the philanthropic and strategic arms of the Tata empire and enhances his ability to shape key decisions within both the charities and the conglomerate.For months, tensions had simmered within the Trusts with Mistry being seen by some trustees as slowing down decision-making. His exit, they say, restores clarity and authority to the leadership. Divisions became evident in September after non-nominee directors led by Mistry blocked reappointment of Vijay Singh as a nominee director of Trusts on Tata Sons board. The move followed a review of nominee directors who have reached 75 years. Noel and Venu, the other two nominee trustees, didn’t support Singh’s removal. Non-nominee directors suggested Mistry as Singh’s replacement but Noel rejected it. Consequently, Singh, 77, resigned from the board of Tata Sons. With the tradition of unanimity first broken by the Mistry faction, Noel along with Srinivasan and Vijay Singh chose not to approve Mistry’s reappointment as a lifelong trustee on the boards of the charities. Mistry had maintained his reappointment was a “procedural formality,” referring to a Oct 17, 2024 resolution passed unanimously by the Trusts that said that upon expiry of tenure, a trustee “will be reappointed by the concerned Trust without any limit being attached to the period of tenure.“One trustee who opposed Mistry’s reappointment said: “I cannot agree with Mistry’s suggestion that all reappointments were already approved on Oct 17. The resolutions cannot be interpreted in a way that reduces critical decisions – such as trustee reappointments – to a formality. Such an interpretation is inconsistent with the law and our fiduciary obligations as trustees.”

Another trustee, who also did not back Mistry’s reappointment, wrote, “The decision to reappoint a trustee can never be a procedural formality. Such a suggestion undermines our fiduciary duty and runs contrary to the law.”Three of the other trustees – Pramit Jhaveri, Darius Khambata, and Jehangir Jehangir – had, however, approved Mistry’s reappointment. But with no unanimity among trustees, Mistry’s three-year term came to an end on Tuesday.Since Noel Tata and Venu Srinivasan are already permanent trustees, the trusteeships of Jhaveri, Singh, and Khambata will come up for renewal over time.The Tata Trusts own two-thirds of Tata Sons, the holding company of the group, and under Tata Sons’ Articles of Association, the Trusts have the power to veto major board decisions. Article 121 lists several matters, including the appointment or removal of the chairman, sale of assets, and investments exceeding Rs 100 crore.The non-nominee directors led by Mistry had claimed that they were not being given complete updates on Tata Sons, restricting their ability to make informed decision. The nominee directors maintained they were bound by fiduciary duties to Tata Sons and could not share price-sensitive information about listed companies.Some key issues, including the public listing of Tata Sons, board appointments, and investments in certain group companies, may be revisited following the change in the Trusts’ composition as a result of Mehli’s exit. The RBI will have the final say on the IPO, as Tata Sons has sought an exemption by applying to surrender its core investment company registration.With Mistry’s exit, new trustees are expected to be inducted with an eye on ensuring consensus; there’s no clarity now on whether some existing tenures will be renewed. Mistry could still challenge the Trusts’ decision in court, arguing that three trustees had violated the unanimous Oct 17 resolution stating that on expiry of tenure, a trustee’s term would be renewed for life. But legal experts say the Trusts’ deeds will take precedence in determining the legality of his removal.“The fact that there are two camps with diverse views can itself result in a vociferous feud, which the Tatas as a globally renowned institution can ill-afford,” said senior corporate lawyer Swapnil Kothari. “Absent a clause stipulating permanency, one cannot read a statutory right for permanent trusteeship in the entire framework of corporate laws. Amending the Trust deeds to incorporate permanency could be a Sisyphean task, particularly if the matter becomes sub judice.” Kothari added that clarity in leadership and defined roles were critical to restoring functional smoothness and bridging what he called the current ‘trust deficit.’ “One can only hope wiser counsel prevails and issue is resolved amicably,” he added.