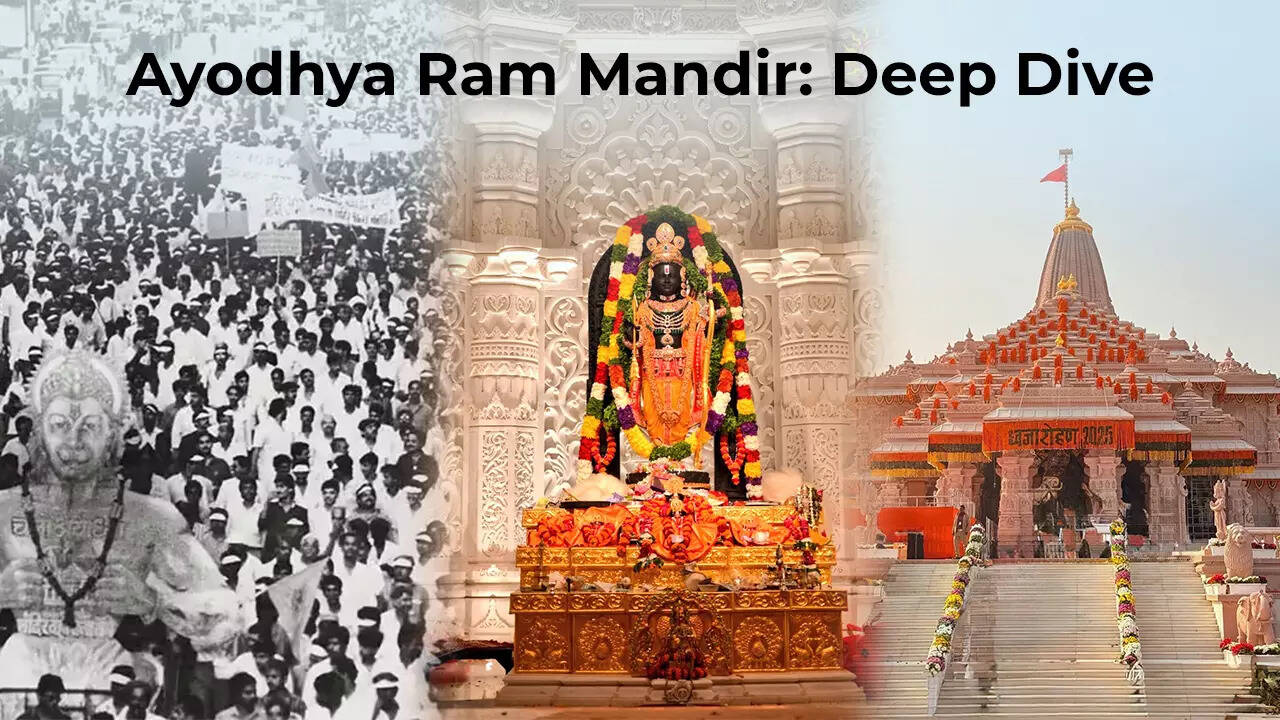

Awadh was aghast. The city collapsed like a lamp about to lose its flame. Men, women and children followed him as though Ayodhya itself was walking away. They did not see a prince going to the forest, it was like something being forcefully torn away with the strings of hope that he might stay hanging loose. The moment he stepped away, the capital of the Kosala kingdom felt emptied of life. This is how Maharishi Valmiki portrays Ram’s departure for his 14-year vanvas in Treta Yuga.The grief that filled Ayodhya in Valmiki’s verses did not stop at the edge of the forest. It travelled through centuries. It lived through kingdoms, invasions and courtrooms. It became devotion and politics. It became movements and marches. The 500-year-long Ram Janmabhoomi struggle was never just about land. It was about bringing Ram back. This time in Kaliyuga.Generations came and went, but the question survived: When will Ram Lalla return?He did return. On January 22, 2024, when the consecration ceremony of the deity was held. What was once a memory in scriptures and prayers finally took form in stone and light. The temple that had lived in longing now stands as faith fulfilled, and a civilisation reclaimed what it never stopped believing was its own.

Key events

November 25, 2025, marked the final milestone with the completion of the temple and a “Dhwajarohan” event, attended by PM Narendra Modi, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat and UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath.Addressing a gathering after the flag hoisting event on November 25, the Prime Minister stated that today the city of Ayodhya is witnessing yet another pinnacle of India’s cultural consciousness.“This Dharma Dhwaja is not merely a flag, but the flag of the renaissance of Indian civilisation,” he said, explaining that its saffron colour, the glory of the Solar dynasty inscribed upon it, the sacred Om depicted, and the engraved Kovidar tree symbolise the greatness of Ram Rajya.

PM Modi during Dhwajarahon event

The story that had begun 500 years ago with the desecration under Mughal invader Babur slowly entered courtrooms, legal arguments and the political landscape. Each petition was an echo of a civilisational longing. Every verdict and every stay order became footsteps in a centuries-long journey.Ayodhya did not forget. Neither did the people who came on foot from distant villages, nor the saints who guarded the belief like a flame, waiting for the Ram Lalla’s temple to rise again.The struggle took different shapes over the centuries. Mahant Raghubir Das and others filed suits not for power or land, but for the right to worship. The movement was still quiet then, but the silence was deceptive. The devotion was gathering strength!The Origin Of The DisputeThe story did not begin with courts or politics. It began in the sixteenth century when the temple at Ram Janmabhoomi was torn down, and a mosque was constructed under Babur’s general, Mir Baqi. The temple was demolished, but the faith was not. Hindus continued to worship at the site. The belief that this was Ram’s birthplace never broke. It lived through devotion, pilgrimage and collective memory.Muslim Chronicles on AyodhyaSeveral works in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu discussed the demolition of the Ramjanmabhumi temple and its replacement by Babri Masjid. In the book “The Ayodhya Temple-Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources” by Harsh Narain, there’s a mention of Al-Hind-u fi al- ‘Ahd al-Islami (India in the Islamic Era) by Maulana Hakim Sayyid Abd al-Hayy, which was translated into Urdu by Maulana Shams Tabriz Khan, under the title Hindustan Islami Ahd mein.

Excerpt – The Ayodhya Temple-Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources

In Tarikh-i Awadh (1919), written by Muhammad Najmul Ghani, it is stated: “Babur got the mosque built after demolishing the Janmasthan and used in his mosque the stone of the same Janmasthan, which was richly engraved, precious kasauti stone, and which survives even today.”The Fasanah-I Ibrat, written by Rajab Ali Beg Surur in 1860, but first published in 1884, stated: “…a glorious mosque was built up during King Babar’s regime on the spot where Sita ki Rasoi tomb (?) is situated in Awadh. During this Babari (dispensation) the Hindus had no guts to be a match for the Muslims.Harsh Narain’s work states that the Qaysar-u’t Tawarikh, which is an Urdu historical chronicle that describes the Janmabhoomi demolition and mosque construction, located the Harsh Narain’s work states that the Qaysar-u’t Tawarikh, which is an Urdu historical chronicle that describes the Janmabhoomi demolition and mosque construction, located the mosque in Sita ki Rasoi as well as the Janmasthan. It acknowledged, “…all the temples of Ayodhya were turned into mosques by the Sultans of the past.”European Account on JanmabhoomiIn one of the multiple accounts of foreign travellers, Joseph Tieffenthaler, the Austrian Jesuit, who stayed in India from 1743 till his death some four decades later, toured Awadh between 1766 and 1771. According to Meenakshi Jain’s The Battle For Rama work, he was the first to refer to the destruction of a temple at Rama’s birthplace by a Mughal ruler. He saw Hindus worshipping a religious structure in the form of a vedi (cradle) in the premises, but said nothing about Muslims offering namaaz. He also noted the large gatherings of Hindus on the occasion of Rama Navami (Rama’s birthday). He wrote: “Emperor Aurenzgebe got the fortress called Ramcot demolished and got a Muslim temple, with triple domes, constructed at the same place. Others say that it was constructed by ‘Babor’…”Tieffenthaler also provided the earliest European documentation of the Hindu Janmasthan platform, which was later called “Ram Chabutra”.

Account of Joseph Tieffenthaler

He futher writes: “However, there still exists some superstitious cult in some place or other. For example, in the place where the native house of Ram existed, they go around 3 times and prostrate on the floor. The two spots are surrounded by a low wall constructed with battlements. One enters the front hall through a low semi-circular door… On the 24th of the Tschet month, a big gathering of people is done here to celebrate the birthday of Ram, so famous in the entire India.”As dynasties and empires changed, the sacredness of the Janmabhoomi did not fade. The temple had fallen, but the birthplace was not forgotten. Devotion shifted to the Ram Chabutra in the outer courtyard, where pilgrims prayed, and saints kept vigil. Akharas, fairs and local traditions kept the belief alive.Struggle During British RuleWhen the British arrived in the mid-1850s, they did not end the conflict. They fenced the site into two courtyards. Muslims offered namaz inside, while Hindus worshipped at the Ram Chabutra outside. The land had one history but two claims.In 1885, Mahant Raghubar Das filed the first suit to build a temple, but it was rejected. However, the worship continued.In 1934, clashes damaged the mosque, and the British repaired it, still avoiding the core question. The dispute remained unresolved and alive.

A rough sketch of the mosque and the Ram Chabutra in its compound.

Post-Independence Legal BattleIndependence did not settle Ayodhya. In December 1949, idols of Ram Lalla were found inside the disputed structure. Authorities sealed it and declared the site disputed. The idol stayed inside, and worship continued from outside, while namaz stopped. In 1950, Gopal Singh Visharad and Paramhans Ramchandra Das filed suits seeking worship inside. More cases followed: Nirmohi Akhara in 1959 claimed management rights, and the Sunni Waqf Board in 1961 contested the property. The courts froze the status quo. The fight moved from streets to case files, petitions and orders.

Ram Janmabhoomi Dispute

The Unlocking That Changed IndiaBy the 1980s, the dispute had moved beyond the courtroom. The VHP adopted the Ram Janmabhoomi cause, and the RSS gave the campaign nationwide strength. The turning point came in 1986 when the Faizabad court ordered the gates of the structure to be opened, and the government allowed it. Within hours, darshan began, and Hindus entered after decades. Namaz did not resume. A locked shrine became an open site of worship, and the dispute that had waited behind iron bars stepped into public life.

Events after 1986

The opening of the gates in 1986 changed more than access to the temple. It changed the direction of Indian politics and public sentiment. For decades the issue had been faith and legal argument. Now it became a movement that spread into homes, streets and television screens. The telecast of Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan in 1987–88 turned the story of Ram into a national cultural moment. Families paused their Sundays to watch it. Streets emptied. Temples saw new crowds. Faith acquired momentum, and the Ram Janmabhoomi question began entering everyday life.

Photo: Family watching Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan on Sunday morning – 1987

In 1989, the VHP laid the foundation stone (shilanyas) near the disputed site with the approval of the Rajiv Gandhi government, and the issue moved further into national consciousness. The same year, the BJP officially adopted the Ram Mandir demand through the Palampur Resolution. A religious and cultural movement had now gained a clear political face.

Photo: VHP along with its supporters and BJP a huge rally at the disputed site in Ayodhya.

In 1990, LK Advani launched the Rath Yatra from Somnath to Ayodhya, mobilising lakhs of supporters across the country.

Photo: Advani’s Rath Yatra from Somnath to Ayodhya

The yatra provoked a counter-mobilisation and heightened tensions. When Kar Sevaks attempted to move towards the disputed site, the Uttar Pradesh government under Mulayam Singh Yadav ordered police firing. Several kar sevaks were killed. The movement intensified further.

Photo: The Kothari brothers, Ram and Sharad Kothari, were two young men from Kolkata who were killed by police firing in Ayodhya on November 2, 1990

From late November 1992, lakhs of kar sevaks had gathered in Ayodhya under multiple Hindu organisations. The call for kar seva had built expectations that something decisive would happen on the ground. The events reached a climax on 6 December 1992. Crowds demolished the disputed structure, which opened a new chapter of religious, political and legal conflict.

Photo: Kar Sevaks at the dispute structure on December 6, 1992

After the incident, the court cases multiplied. Commissions were formed. What began as a locked shrine had turned into one of the defining movements of modern India.

Post 1986 Mandir Movement

After the 1992 demolition, the dispute shifted permanently into the courts. The central government acquired the site in 1993 and asked the Supreme Court to settle ownership. The title suits were transferred to the Allahabad high court, which examined archaeological, historical and documentary evidence. The 2003 ASI excavation report remains consistent with a large pre-existing structure below the demolished mosque. In 2010, the high court ruled that the land be divided among three parties, but the judgment was appealed by all sides. The case then moved to the Supreme Court, where a Constitution Bench heard extensive arguments on law, title, belief and history. In November 2019, the top court delivered its final judgment: The land was awarded for the construction of a Ram temple, and an alternative site was directed to be allotted to the Muslim side. The verdict ended the centuries-long legal battle and settled ownership of the Janmabhoomi.

Key points of Supreme Court judgement

After the Supreme Court’s 2019 verdict awarding the disputed land for the construction of a Ram temple, plans for building began in earnest.

Photo: Ram Lalla in a tent before the SC verdict (Left)/ Grand Ram Lalla Mandir in Ayodhya

A trust was formed to oversee development, and construction work proceeded over the next few years with architectural planning, sanctum layout, and preparations for consecration. On 22 January 2024, the new temple was inaugurated with religious ceremonies.

Photo: Ram Lalla idol in the sanctum sanctoram of Ayodhya Mandir

On November 25, the “Dwajarohan” ceremony, hoisting the saffron flag atop the temple, reaffirmed the Mandir’s consecration and the restoration of the wounded civilisation. The long-standing legal and historical dispute thus entered a phase of physical reconstruction and symbolic closure, as devotees welcomed the final restoration of what they regard as their heritage.If one scrolls through the Ram Mandir movement wire-to-wire, the demand for the temple emerges not just as a caravan of facts and emotions, but as a testament to a faith that never faded. Those in the frontline of the movement, especially the Hindu community, continued their worship at the site, whether in the outer courtyard earlier or before the idol after 1949, sustaining an unbroken thread of devotion, which helped in healing and rekindling the oldest civilisation.