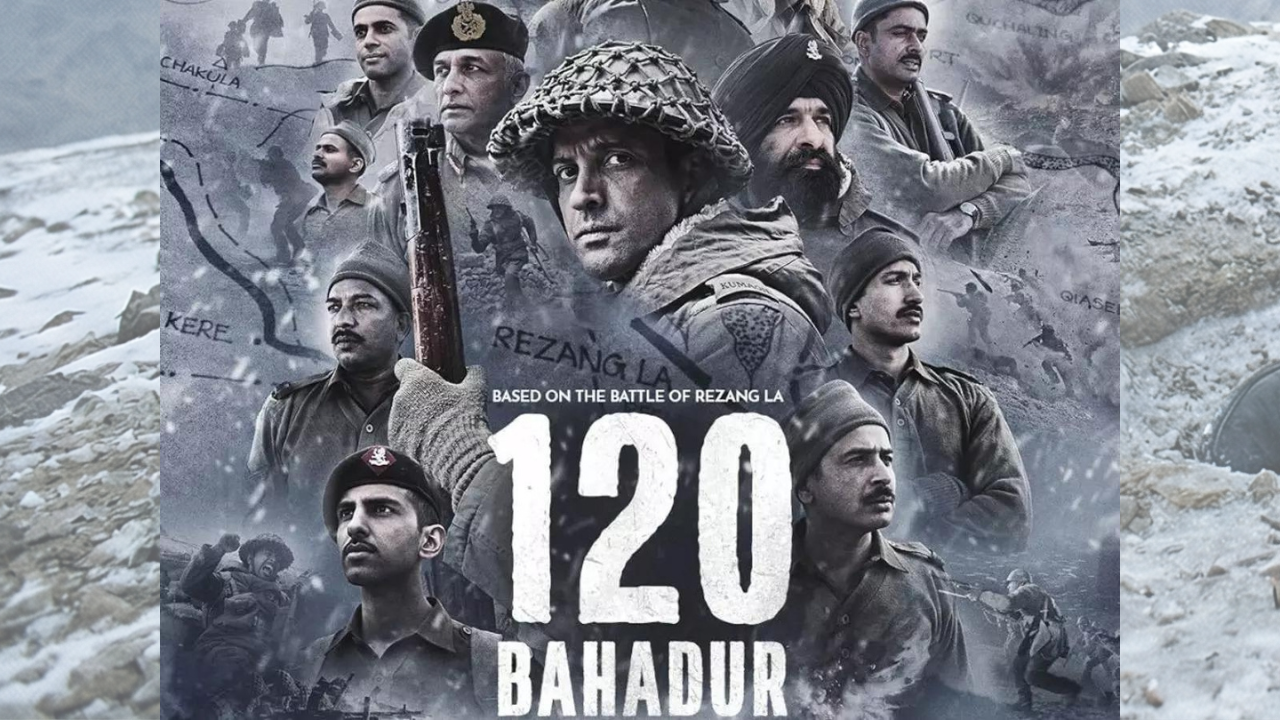

New Delhi: Release of Farhan Akhtar‘120 Bahadur’ has once again brought the famous battle of Rezang La back into the national consciousness. As the film revisits an episode etched in Indian military history, the story goes far beyond cinema – it is a retelling of courage, cold winds, last bullets and men who refused to back down. On 18 November 1962, in the dead of winter of the Sino-Indian War, 120 soldiers of Charlie Company, 13 Kumaon Regiment – composed almost entirely of Ahir warriors – faced a Chinese attack approximately twenty-five times larger. The battalion remained stationed at Rezang La at such a height where even breathing was difficult. They fought covered in snow, outnumbered in terrain with no place to hide. Although only a handful of them survived, they left behind a legacy that became immortal not only in regimental history but also in the military soul of India.

This feature brings together the strategic background, flow of the war, those who led it, those who fell, the geography that shaped it, the testimony of survivors, the political consequences and living memory that continues beyond the memorials. It tells how 120 men, cut off from reinforcements and artillery, held off a 3,000-strong Chinese army – inflicting mass casualties of over 1,300 – and how Major Shaitan Singh became one of India’s greatest battlefield icons.

Rejang La before the battle

The Sino-Indian War of 1962 was the culmination of years of mistrust, border disagreements and strategic tensions. India followed the McMahon Line drawn in the early 20th century, while China rejected it, claiming large parts of Aksai Chin and the North-East Frontier Agency. Tensions intensified from 1959 onwards, with patrol skirmishes turning into wider conflict. India’s “Forward Policy” placed troops close to disputed areas in hopes of stopping China’s advance, yet it also underestimated China’s operational planning and infrastructure advantages.

In Ladakh, the stakes were especially high. Control over Aksai Chin provided China with a corridor linking Xinjiang with Tibet – vital for logistics movement. India, realizing the vulnerability of Leh and Chushul airstrips, attempted to block potential invasion routes through the desolate valley. Rezang La, standing like a windswept sentry at 16,000-18,000 feet, became the southern base of Indian defence.Capturing Rezang La was like capturing Ladakh. Losing it meant exposing the route to Chushul to danger.

The land where the heroes stood: territory and the struggle for survival

Rejang La is not just a battlefield – it is a test of the human body. The land offers nothing: no trees, no cover, only strong winds whipping against stones. The temperature drops to extremely low levels in November. Dilute oxygen. The heart starts beating fast. Man’s breath appears like frost.Indian positions consisted of shallow trenches, rock formations, and weapon pits cut into the frozen ground. The night temperature dropped well below zero, which was many times slower than enemy gunfire. The soldiers here fought two wars simultaneously – one against China, the other against nature.

Ammunition was limited. The jackets were thin. Reinforcement was not possible. The helicopter could barely hover. Men keep warm from movement, and if they sit too long, sleep itself becomes fatal.Nevertheless they maintained control over the mountain ranges, because India’s progress depended on it.

Charlie Company and command of Major Shaitan Singh

Charlie Company of 13 Kumaon Regiment, consisting mainly of Ahir soldiers from Haryana and Rajasthan, served as a cohesive infantry unit accustomed to hardships and high morale at Rezang La. The men shared cultural ties, language, and rural backgrounds, which strengthened group cohesion and battlefield trust. Their commanding officer, Major Shaitan Singh Bhati, was known for a firm command style balanced with approachability and personal example – traits that would become decisive during the war.

The company deployed about 120 soldiers in several platoon positions at Rezang La, each manned to guard the key approach routes from the Chinese side. Light machine guns, mortars and rifles were strategically deployed for overlapping fields of fire, wherever the terrain permitted. However, the mountainous landscape left some parts exposed and created blind spots that the attacking force could later exploit. Despite these challenges, the unit maintained defensive readiness with the understanding that reinforcements were unlikely and withdrawal was not part of the plan.Within Charlie Company, the hope was not for survival but for resistance. The men were told that in the event of an attack, they were to hold their positions as long as ammunition and manpower permitted. It was a defensive stance designed to protect Chushul and delay or hinder any breakthrough into the Ladakh region.

Night of 17 November 1962: preparations for the attack

On 17 November, conditions at Rezang La remained cold, calm and confusing, and there was no clear sign of immediate action. However, intelligence and observations suggest increased Chinese activity in the region. During the night, Chinese forces consolidated their forces down the ridge, bringing forward infantry units estimated at over 3000 soldiers along with supporting elements equipped with mortars, artillery and heavy machine guns.The Chinese tactical plan was structured around an initial bombardment followed by a direct infantry attack. Without access to night-vision systems, early-warning radar or adequate surveillance technology, Indian defenders relied on routine surveillance, patrol reports and anticipation. Communications were maintained through field telephones which later became vulnerable to shellfire.For Charlie Company, the night passed in hopes that contact might be made at first light. Ammunition was distributed, positions were fortified where possible, and commanders reviewed arcs of fire and fallback points inside the fixed perimeter. Although the atmosphere was superficially calm, there was a sense among the people that a major event was imminent.

18 November – Initial phase of the Battle of Rezang La

The battle began just before dawn, with Chinese artillery and mortar fire concentrated on Indian positions. The bombardment damaged the protective stone works, cut communication lines between platoons and left little opportunity for movement or reorganisation. Despite the intensity of the shelling, the defensive line remained intact and no post was abandoned.

Major Shaitan Singh was injured by an MMG burst in the stomach at around 5.30 in the morning. He sat on a stone, tied his intestines with his turban and kept shouting, ‘Keep fighting, keep fighting.’ He died at the command post at 8:15 am. Even in May 1963, we had found his body standing straight – frozen like a statue.

Nursing Assistant Nihal Singh (died 2023)

Once the barrage was lifted, a massive infantry attack began. Chinese troops advanced across open ground and attempted several communication routes. Charlie Company returned fire with rifles, LMGs and available mortars, causing heavy losses to the advancing groups. The initial attacks were successfully repulsed, but the attack did not stop. Fresh waves came one after another, putting pressure on every forward position.

Representative AI image: (After the battle, when recovery teams reached Rejang La, they found the soldiers still in their firing positions – rifles clutched, bodies frozen solid, eyes fixed on the direction from which the enemy had come. It seemed as if time had stopped at the moment of their last act of resistance.)

As the morning approached, Chinese troops changed tactics, probing for gaps, testing blind spots in the Indian fire coverage and attacking from multiple directions. The defenders, unable to reorganize beyond trench-level coordination due to communications disruption, continued to maintain fire discipline and engage targets within range. With retreat across open terrain impossible, the company maintained its defense through constant engagement.

Transition to close combat and progressive erosion

Fighting intensified as Chinese forces closed in on individual outposts, using ravines, dead lands and terrain folds to reach positions safe from direct observation. The engagement distance decreased, forcing several platoons into close combat. As ammunition stores began to deplete, bayonets, hand grenades and hand-to-hand combat became common.Most riflemen expended their entire allotment of about 100 cartridges during the long battle. As small arms fire became rare, the defenders continued to resist using bayonets and available melee methods. Bodies recovered later revealed that many soldiers had died facing forward with bayonets drawn, indicating last-ditch resistance despite running out of ammunition.The constant firing overheated the weapon’s barrels, the trenches could be overrun only after prolonged resistance, and platoon positions fell one by one only due to encirclement or casualty losses. There is no record of surrender from any post, and battlefield findings indicate that units held out until they were physically unable to continue.

Major Shaitan Singh: Leadership carved in ice

Major Shaitan Singh refused to stay at the headquarters. He moved from post to post across open terrain under machine-gun fire, rallying men, changing squads, giving orders that ensured no flank was destroyed. He was everywhere at the same time – limping through shrapnel, bleeding, screaming through the air and the bullet holes.He was hit several times. When evacuation was suggested, he refused – he did not want to risk the lives of those who would carry him. He stayed safe from the rocks, still giving instructions, still remaining a commander, even as life faded.

We were 120, they were thousands. When the last bullet was fired we deployed bayonets. Major Saheb came limping, bleeding from his stomach and said, ‘You are Ahir, get buried in the dust but do not step back.’ We kept fighting until the sun went down. When I woke up I was in a Chinese hospital.

Sepoy Ram Chander (died 2022)

His body, recovered months later, was found standing upright – frozen like the silent sentinel of Rezang La.For this last stand he posthumously received the Param Vir Chakra.Almost all of the 120 on board died. Only five survived – all injured, captured and released in 1963. The Chinese captured Rezang La, but at a heavy cost – casualties are estimated at over 1300 by Charlie Company alone. Seldom in modern history has a small unit caused so much damage to such a large army.When India returned months after the ceasefire, they found bodies still in firing positions – rifles pointing outwards, fingers frozen on the trigger. An entire company had died just as it had fought.

Each man had fired his full 100 rounds. Many had 10-15 Chinese bayonet wounds on their bodies. My platoon commander Lieutenant Gopal Singh had 14 bullets in his body and his Sten gun was bent due to collision with the Chinese.

constable sumer singh

Remembering Rejang La: Monuments and Memories

At Chushul stands a war memorial, exposed to the cold and wind on a hill, with the names of those who died inscribed on it. Veterans and families come every year. So too are the soldiers stationed nearby, many of whom have left behind their regimental badges or gloves – small tributes to the brave men whose bones once lay in that snow.Statues and institutions in Haryana and Rajasthan bear his name. Regiments teach war to every young soldier. It is no longer just a war story – it is a military treatise.

Rezang La in India’s national narrative

The 1962 war remains a scar in India’s strategic memory – a war where planning failed, equipment was scarce and diplomacy collapsed. Yet Rezang La shines within it like a flame that cannot be extinguished. It represents not defeat, but moral victory. It tells the youth that courage is not measured by the weapon in hand, but by the refusal to back down.It tells the nation that even when the last shot is fired, a soldier still has his body to give.(with inputs Colonel Ajay Singh’s The Battle of Rezang La (2021), the Indian Army documentary Rezang La (2022) and interviews given to Doordarshan and All India Radio.)