John SimpsonBBC world affairs editor

BBC

BBCSensitive content: This article contains a graphic description of death that some readers may find upsetting

I’ve reported on more than 40 wars around the world during my career, which goes back to the 1960s. I watched the Cold War reach its height, then simply evaporate. But I’ve never seen a year quite as worrying as 2025 has been – not just because several major conflicts are raging but because it is becoming clear that one of them has geopolitical implications of unparalleled importance.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky has warned that the current conflict in his country could escalate into a world war. After nearly 60 years of observing conflict, I’ve got a nasty feeling he’s right.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesNato governments are on high alert for any signs that Russia is cutting the undersea cables that carry the electronic traffic that keeps Western society going. Their drones are accused of testing the defences of Nato countries. Their hackers develop ways of putting ministries, emergency services and huge corporations out of operation.

Authorities in the west are certain Russia’s secret services murder and attempt to murder dissidents who have taken refuge in the West. An inquiry into the attempted murder in Salisbury of the former Russian intelligence agent Sergei Skrypal in 2018 (plus the actual fatal poisoning of a local woman, Dawn Sturgess) concluded that the attack had been agreed at the highest level in Russia. That means President Putin himself.

This time feels different

The year 2025 has been marked by three very different wars. There is Ukraine of course, where the UN says 14,000 civilians have died. In Gaza, where Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu promised “mighty vengeance” after about 1,200 people were killed when Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October 2023 and 251 people were taken hostage.

Since then, more than 70,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli military action, including more than 30,000 women and children according to Gaza’s Hamas-run health ministry – figures the UN considers reliable.

Meanwhile there has been a ferocious civil war between two military factions in Sudan. More than 150,000 people have been killed there over the past couple of years; around 12 million have been forced out of their homes.

Maybe, if this had been the only war in 2025, the outside world would have done more to stop it; but it wasn’t.

“I’m good at solving wars,” said US President Donald Trump, as his aircraft flew him to Israel after he had negotiated a ceasefire in the Gaza fighting. It’s true that fewer people are dying in Gaza now. Despite the ceasefire, the Gaza war certainly doesn’t feel as though it’s been solved.

Given the appalling suffering in the Middle East it may sound strange to say the war in Ukraine is on a completely different level to this. But it is.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe Cold War aside, most of the conflicts I’ve covered over the years have been small-scale affairs: nasty and dangerous, certainly, but not serious enough to threaten the peace of the entire world. Some conflicts, such as Vietnam, the first Gulf War, and the war in Kosovo, did occasionally look as though they might tip over into something much worse, but they never did.

The great powers were too nervous about the dangers that a localised, conventional war might turn into a nuclear one.

“I’m not going to start the Third World War for you,” the British Gen Sir Mike Jackson reportedly shouted over his radio in Kosovo in 1999, when his Nato superior ordered British and French forces to seize an airfield in Pristina after the Russian troops had got there first.

In the coming year, 2026, though, Russia, noting President Trump’s apparent lack of interest in Europe, seems ready and willing to push for much greater dominance.

Earlier this month, Putin said Russia was not planning to go to war with Europe, but was ready “right now” if Europeans wanted to.

At a later televised event he said: “There won’t be any operations if you treat us with respect, if you respect our interests just as we’ve always tried to respect yours”.

Getty Images

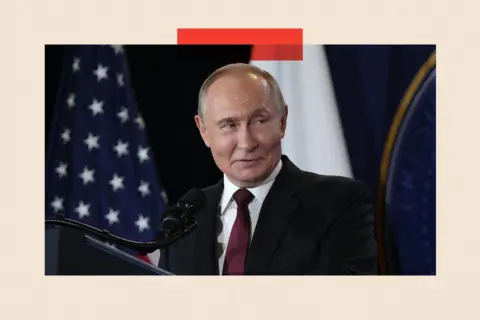

Getty ImagesBut already Russia, a major world power, has invaded an independent European country, resulting in huge numbers of civilian and also military deaths. It is accused by Ukraine of kidnapping at least 20,000 children. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin for his involvement in this, something Russia has always denied.

Russia says it invaded in order to protect itself against Nato encroachment, but President Putin has indicated another motive: the desire to restore Russia’s regional sphere of influence.

American disapproval

He is gratefully aware that this last year, 2025, has seen something most Western countries had regarded as unthinkable: the possibility that an American president might turn his back on the strategic system which has been in force ever since World War Two.

Not only is Washington now uncertain it wants to protect Europe, it disapproves of the direction it believes Europe is heading in. The Trump administration’s new national security strategy report claims Europe now faces the “stark prospect of civilisational erasure”.

The Kremlin welcomed the report, saying it is consistent with Russia’s own vision. You bet it is.

Inside Russia, Putin has silenced most internal opposition to himself and to the Ukraine war, according to the UN special rapporteur focusing on human rights in Russia. He’s got his own problems, though: the possibility of inflation rising again after a recent cooling, oil revenues falling, and his government having had to raise VAT to help pay for the war.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe economies of the European Union are 10 times bigger than Russia’s; even more than that if you add the UK. The combined European population of 450 million, is over three times Russia’s 145 million. Still, Western Europe has seemed nervous of losing its creature comforts, and was until recently reluctant to pay for its own defence as long as America can be persuaded to protect it.

America, too, is different nowadays: less influential, more inward-looking, and increasingly different from the America I’ve reported on for my entire career. Now, very much as in the 1920s and 30s, it wants to concentrate on its own national interests.

Even if President Trump loses a lot of his political strength at next year’s mid-term elections, he may have shifted the dial so far towards isolationism that even a more Nato-minded American president in 2028 might find it hard to come to Europe’s aid.

Don’t think Vladimir Putin hasn’t noticed that.

The risk of escalation

The coming year, 2026, does look as though it’ll be important. Zelensky may well feel obliged to agree to a peace deal, carving off a large part of Ukrainian territory. Will there be enough bankable guarantees to stop President Putin coming back for more in a few years’ time?

For Ukraine and its European supporters, already feeling that they are at war with Russia, that’s an important question. Europe will have to take over a far greater share of keeping Ukraine going, but if the United States turns its back on Ukraine, as it sometimes threatens to do, that will be a colossal burden.

Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Global Images Ukraine via Getty ImagesBut could the war turn into a nuclear confrontation?

We know President Putin is a gambler; a more careful leader would have shied away from invading Ukraine in February 2022. His henchmen make bloodcurdling threats about wiping the UK and other European countries off the map with Russia’s vaunted new weapons, but he’s usually much more restrained himself.

While the Americans are still active members of Nato, the risk that they could respond with a devastating nuclear attack of their own is still too great. For now.

China’s global role

As for China, President Xi Jinping has made few outright threats against the self-governed island of Taiwan recently. But two years ago the then director of the CIA William Burns said Xi Jinping had ordered the People’s Liberation Army to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. If China doesn’t take some sort of decisive action to claim Taiwan, Xi Jinping could consider this to look pretty feeble. He won’t want that.

You might think that China is too strong and wealthy nowadays to worry about domestic public opinion. Not so. Ever since the uprising against Deng Xiaoping in 1989, which ended with the Tiananmen massacre, Chinese leaders have monitored the way the country reacts with obsessive care.

I watched the events unfold in Tiananmen myself, reporting and even sometimes living in the Square.

AFP via Getty Images, Sputnik, Pool

AFP via Getty Images, Sputnik, PoolThe story of 4 June 1989 wasn’t as simple as we thought at the time: armed soldiers shooting down unarmed students. That certainly happened, but there was another battle going on in Beijing and many other Chinese cities. Thousands of ordinary working-class people came out onto the streets, determined to use the attack on the students as a chance to overthrow the control of the Chinese Communist Party altogether.

When I drove through the streets two days later, I saw at least five police stations and three local security police headquarters burned out. In one suburb the angry crowd had set fire to a policeman and propped up his charred body against a wall. A uniform cap was put at a jaunty angle on his head, and a cigarette had been stuck between his blackened lips.

It turns out the army wasn’t just putting down a long-standing demonstration by students, it was stamping out a popular uprising by ordinary Chinese people.

China’s political leadership, still unable to bury the memories of what happened 36 years ago, is constantly on the look-out for signs of opposition – whether from organised groups like Falun Gong or the independent Christian church or the democracy movement in Hong Kong, or just people demonstrating against local corruption. All are stamped on with great force.

I have spent a good deal of time reporting on China since 1989, watching its rise to economic and political dominance. I even came to know a top politician who was Xi Jinping’s rival and competitor. His name was Bo Xilai, and he was an anglophile who spoke surprisingly openly about China’s politics.

He once said to me, “You’ll never understand how insecure a government feels when it knows it hasn’t been elected.”

As for Bo Xilai, he was jailed for life in 2013 after being found guilty of bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power.

Altogether, then, 2026 looks like being an important year. China’s strength will grow, and its strategy for taking over Taiwan – Xi Jinping’s great ambition – will become clearer. It may be that the war in Ukraine will be settled, but on terms that are favourable to President Putin.

He may be free to come back for more Ukrainian territory when he’s ready. And President Trump, even though his political wings could be clipped in November’s mid-term elections, will distance the US from Europe even more.

From the European point of view, the outlook could scarcely be more gloomy.

If you thought World War Three would be a shooting-match with nuclear weapons, think again. It’s much more likely to be a collection of diplomatic and military manoeuvres, which will see autocracy flourish. It could even threaten to break up the Western alliance.

And the process has already started.

Top picture credits: AFP / Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.