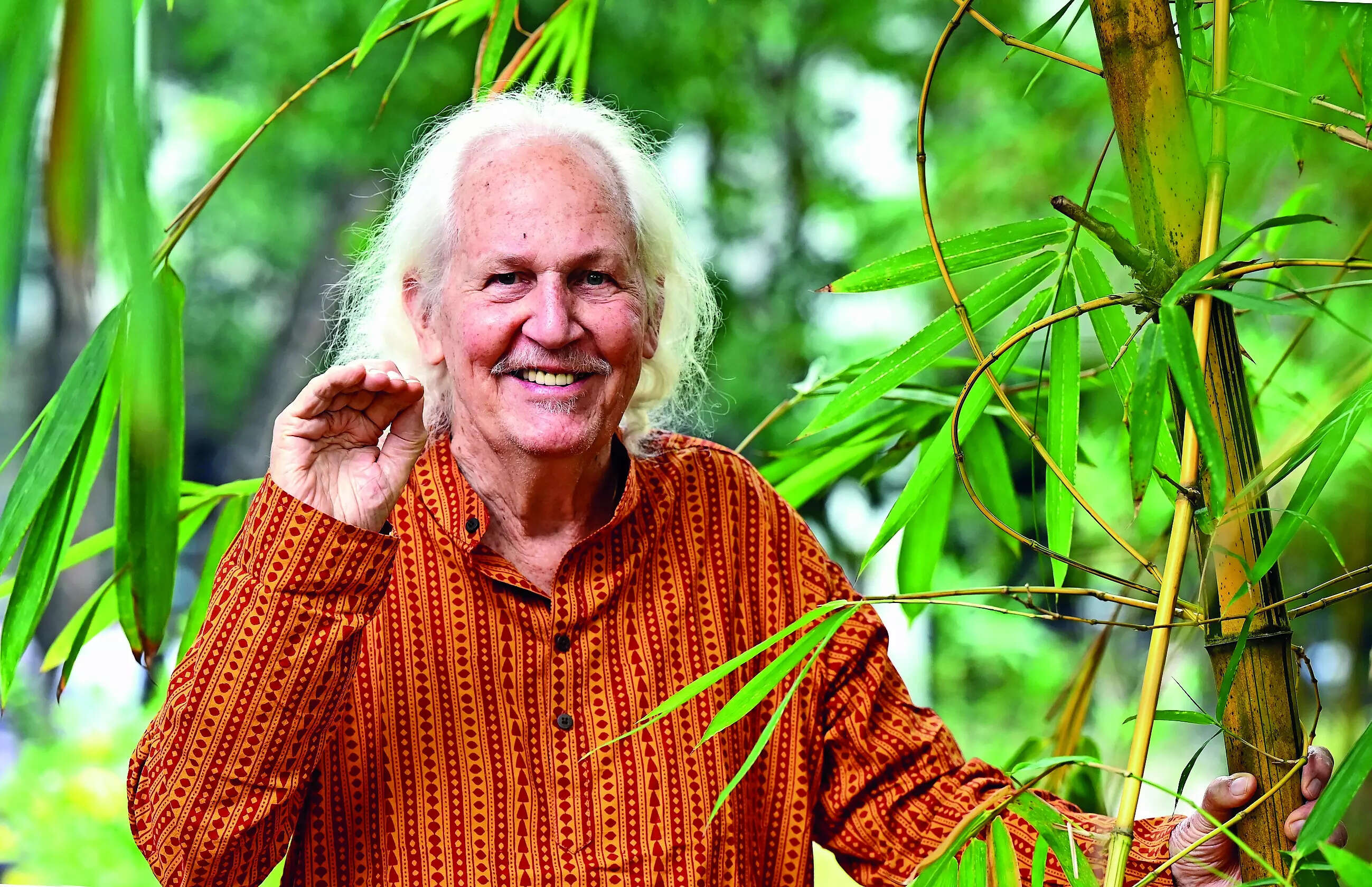

A tiger appeared without warning, gliding like a shadow along the forest edge, just as a boat was sailing in the Periyar waters. For a 13-year-old boy traveling to Kerala in 1957, the moment was electrifying. Then wildlife was not limited to sanctuaries only; It was woven into the visible, immediate, everyday landscape. that fleeting meeting remained with Romulus Whittaker Long before he became one of India’s most influential conservationists, he shaped a life dedicated to understanding and protecting creatures most people feared. Whittaker’s first visit to Kerala was part of a family trip. His sister was graduating from high school, and the itinerary included Kochi, where they stayed at the Malabar Hotel, considered the finest hotel in the city at the time. Boat rides on rivers such as the Periyar were already popular, and wildlife sightings were common. “Gaur and deer were easily sighted, and tigers roamed freely even at a time when hunting was legal. I never saw a king cobra on that trip, but the habit of taking a closer look was already ingrained,” recalls Whittaker. That attraction was created long before India. Growing up in northern New York state, Whittaker once watched neighborhood boys kill a snake out of fear. “I knew more about snakes than other kids, and that made a difference,” he says. His mother encouraged his curiosity and bought him a book on snakes that helped replace fear with knowledge. Later when he brought home a live snake, instead of getting nervous, he praised it and called it beautiful. An old aquarium with broken glass became a makeshift enclosure. Without realizing it, Whittaker had taken his first steps toward a lifelong connection with reptiles – a fascination that deepened after his family moved to India in the 1950s. Janaki Lenin, Whittaker’s partner and co-author of his autobiography “Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll: My Early Years”, says that writing the book gave her a deeper understanding of the extraordinary life he lived. She explains that her schooling was anything but traditional – camping in the forests, fishing in the lakes and once she even found a python under her bed. Boredom was never an option. If a class fails to attract his attention, he simply goes out to explore something more attractive. Comparing his life to hers, Lenin described Whittaker as a man who “has lived six or seven lives at the same time.” Formal education never suited him. After finishing school, Whittaker enrolled in college, but soon realized that classrooms could not compete with hands-on learning. His real education began at the Miami Serpentarium under Bill Haast, the renowned snake handler who pioneered envenoming in the United States. Working with Haast, Whittaker learned how to handle venomous snakes, keep them in captivity, and extract venom for medical use. “Bill Haast was my mentor,” he says. “He taught me not just technique, but to respect snakes.” When Whittaker returned to India, he had a clear idea in mind: the country needed a place where people could learn about snakes scientifically instead of blindly fearing them. That idea took shape in 1969 with the opening of the Madras Snake Park. Visitors arrived apprehensively—some expecting a spectacle, others expecting danger. Whittaker was often seen as an eccentric outsider. But the park was never meant for entertainment. This was an educational experiment. For the first time, ordinary people could see snakes up close, learn to identify species, and understand that most snakes were not out to harm them. Over the decades, the impact has been profound. There are thousands of snake rescuers in India today, Whittaker views this reality with cautious optimism. While rescue operations have reduced routine killings, in some cases it has also become executional. He said Kerala is known for institutionalizing rescue operations. By registering rescuers, issuing identity cards and maintaining an online database, the state has created a system rooted in accountability and data. This model has been adopted and replicated by Karnataka Tamil Nadu, However, snakebite remains one of India’s least recognized public health crises. For decades, official statistics have claimed about 1,400 deaths annually. A nationwide “Million Deaths Study” based on oral autopsies revealed a very grim reality: more than 50,000 deaths each year, with approximately one million snakebite incidents. Many victims never reach a hospital, either dying en route or seeking traditional treatment rather than medical treatment. “The key word is prevention,” says Whittaker. Simple measures – using a torch at night, wearing shoes, being alert near pump houses – can prevent a significant proportion of bites. He further said that better reporting makes it appear that cases are increasing, when in reality awareness and documentation has improved. The biggest challenge remains to treat snakebite as a medical emergency rather than a cultural or mystical phenomenon. Few initiatives better reflect Whittaker’s belief in practical, science-based solutions than his long association with the Irula tribal community of Tamil Nadu. For generations, the Irula survived by capturing snakes for their skins. When the leather trade was banned, their livelihood disappeared overnight. Working with the community, Whittaker helped develop a new model: Irula snake catchers would capture the snakes, extract the venom under controlled conditions and release them back into the wild. The venom will then be supplied to pharmaceutical companies to make antivenom. “They’re saving millions of human lives,” says Whittaker. Today, about 350 Irula families supply venom that meets India’s entire antivenom requirement. To them, it is the only true example of sustainable wildlife use in the country – one that benefits both people and animals without reducing wild populations. Human-animal conflict is one of the most complex conservation challenges. Tiger, leopard and crocodile populations have increased in India – a remarkable achievement by global standards. But many of these animals now live outside protected forests. Leopards, in particular, thrive in agricultural landscapes, raising cubs in sugarcane fields and eating small animals and stray dogs. “Leopards don’t need forests like we think,” explains Whittaker. “They have adapted to living with people.” Problems arise when humanitarian panic leads to occupation and transfer – an intervention that often makes conflict worse. Whittaker’s own experience reinforced this lesson. While living on a small farm near Chennai, he once lost a dog to a leopard. His first instinct was to call the forest department. Then realized: “We moved into his area. He didn’t move into our area.” Simple precautions like keeping dogs indoors at night solved the problem without putting the cat in danger. Lenin agrees that human-wildlife conflict is nothing new, but says its nature has changed. Previously, communities managed negotiations at the local level. “The law took away that freedom, but the state did not fulfill its responsibility to address the issue,” she says. He argues that many conflicts today are effectively created by the state – particularly in the case of elephants, which require vast landscapes and abundant food. Habitat disruption Marginalized communities have to bear the burden of co-existence, even if they are the least equipped to do so. Whittaker is critical of how post-harvest wildlife is managed, particularly in Kerala, one of the few states where wild boars that destroy farms are legally allowed to be killed, but must then be buried. Recalling ecologist Madhav Gadgil’s public criticism of the policy, Whittaker questions the logic of wasting a valuable protein source. “These animals can destroy paddy or groundnut fields as much as an elephant does, but after killing them, you are asked to bury the meat. Especially in rural areas, people always need protein. He mentions seeing electric fences in parts of North India where nilgai, jackal and peacock were killed indiscriminately and left to rot. For them, science-based preventive infrastructure works far better than reactionary measures. He considers Indira Gandhi to be India’s most conservationist prime minister, who played a key role in legislation such as the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972. “She came to the Snake Park in Madras in 1972, and that’s when we told her about the problems we were having. When Rajiv became Prime Minister, we talked to him about the Andamans and the deforestation there, and he stopped it. These were the times when you could actually talk to a Prime Minister and the next day you could see some action; I would love to see that happening today., When Whittaker received the Padma Shri, he briefly met the Prime Minister Narendra Modi But did not get a chance to speak in detail. Later he sent a draft message to the PM’s office hoping to find a mention about prevention of snakebites during Mann Ki Baat. “If the Prime Minister, even for a minute, treated snakebite as a medical emergency and talked about the importance of equipping government hospitals to deal with it, thousands of lives could be saved,” he says. When he first documented the snakes of India, about 275 species were known. Today, more than 360 have been recorded. For young people entering herpetology, he sees unprecedented opportunities through universities and research institutes. “Go out there, volunteer and learn,” he advises. “Observe, respect, and don’t try to be a hero. Conservation is about patience and understanding, not spectacle.” Now in his eighties, Whittaker focuses on snakebite mitigation through films and awareness campaigns. From a child protecting a snake to a man who has spent his entire life inspiring a nation to rethink its fears, his story is ultimately about understanding nature and choosing scientific knowledge over fear. (Romulus Whitaker was in Kochi for the Climate Literature Festival at the Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies with his fellow writer Janaki Lenin)