Mamata Banerjee And his Trinamool Congress has launched an all-out attack against the Election Commission over the process of Special Intensive Review (SIR) ahead of the upcoming assembly elections in the state. True to her style, Mamata has led this movement from the front and united the entire party cadre to fight the change in the voter list. Mamata is not new to this aggressive brand of politics. Throughout her political career, Mamata has seen people taking to the streets to fight their political battles. SIR, which had struggled to dominate elections in Bihar, has become the main issue in Bengal. This is what makes Mamata different from most opposition leaders.

21 July 1993At that time, West Bengal Congress leader Mamata Banerjee was leading a march towards the Writers’ Building in Kolkata. The protest was against the Jyoti Basu-led Left Front government over alleged manipulation of voter lists. Their demand was specific: the introduction of photo identity cards for voters, to curb what the opposition described at the time as “scientific rigging”.

.

The protests escalated further when the police opened fire on the protesters. 13 Congress workers were killed. The police attacked Banerjee, she was thrown out of the Writers Building complex and she suffered serious injuries.

.

The case was not isolated. In another instance, she along with a rape victim sat on a dharna outside the Chief Minister’s residence, demanding action from the Left government. The protest ended with him being pushed and forced.

.

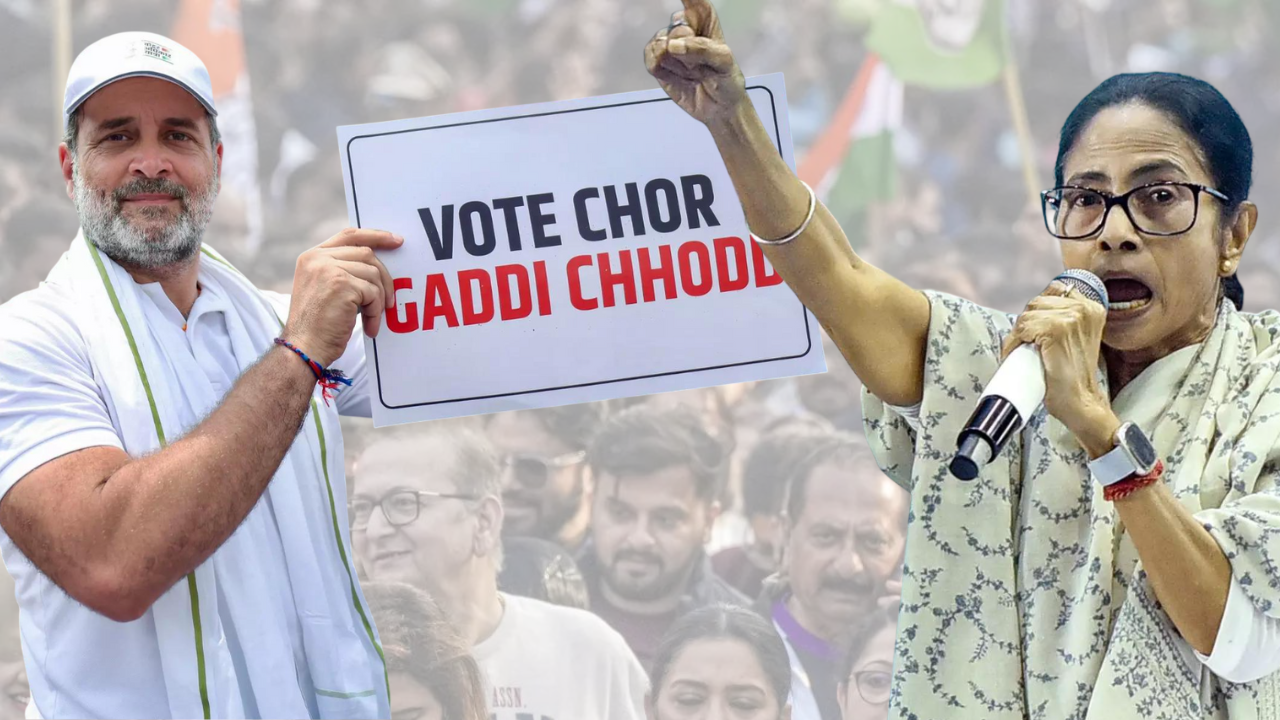

More than three decades later, similar allegations have resurfaced, now defined as “vote theft” and linked to practices such as special intensive vetting (SIR) of voter lists.The difference then and now is not the nature of the allegation, but how political leaders have responded after the allegation was made. This difference is visible in how the opposition Indian faction led Rahul Gandhi And RJD’s Tejashwi Yadav handled the issue in Bihar after last year’s assembly elections, and how Mamata Banerjee is positioning herself in West Bengal ahead of the upcoming elections. In these moments, the charge has traveled much less than the response: While others have raised the charge from the podium and press room, Banerjee has repeatedly chosen to respond through public, grassroots action.What happened in Bihar?In Bihar, the opposition’s take on the “vote theft” narrative began with momentum but proved difficult to sustain.Take the recently held Bihar Assembly elections only. Rahul Gandhi launched the Voters Adhikar Yatra, a campaign to highlight concerns related to the Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of voter lists.The initial phase of the campaign received a noticeable response. The slogan of ‘Vote Chor, Gaddi Chhod’ kept resonating at every stop on the yatra route. This gave momentum to the Congress-led grand alliance to unite. Crowds in urban centers and politically active areas were visible, vocal and angry. For a moment it seemed as if the opposition had found a story that breaks the usual caste calculus.But then, the momentum hit a wall.On the eve of the first phase of voting, Rahul Gandhi tried to play down the allegation. In a high-decibel press conference, he released a dossier titled “H-Files”, which alleged that the Election Commission had acted in ways that systematically favored the NDA. “The Election Commission is not doing its job,” Gandhi declared, warning that the democratic process was being compromised from within.

.

The move made headlines, but it did not lead to much change in the campaign on the ground.As voting began, the Voters’ Rights March failed to transform into a widespread movement. “H-Files” remained largely confined to major prime time news channels but failed to become a rallying point for voters. And then there was silence.In the most crucial phase of the elections – the final phase where undecided voters are turned in – the physical presence of the Congress leadership almost disappeared. While Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah were addressing several rallies across the state, Rahul Gandhi remained absent from the Bihar campaign for a long time.There were no rallies. No road show. Not even virtual presence.According to local party workers, Gandhi’s image quietly disappeared from India Bloc posters in some areas as candidates rearranged their campaign materials in the closing stages. When the results came out, the Congress recorded one of its weakest performances in the recent Bihar elections, limiting the grand alliance’s total seats.Crucially, in the weeks before the election – when allegations of “vote theft” were at their peak – there was no sustained effort to take the issue to the streets. There were no protests near election offices for long. The allegations remained widespread on social media and in passing comments. bengal modelCross the border into West Bengal. With assembly elections approaching in the state, the issue of SIR and “vote theft” is a campaign issue that Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has raised publicly. While the Bihar campaign relied heavily on press conferences and documentation, Banerjee has chosen to place herself at the center of the unfolding confrontation.Take the events of January 9, 2026.When the Enforcement Directorate (ED) raided the offices of I-PAC (Indian Political Action Committee) in Kolkata, the expected political reaction would have been statements and briefings.Mamta Banerjee flipped the script.Within hours of the start of the raid, she reached the I-PAC office, bypassing the central forces and entering the premises. She remained there while the search continued and the confrontation played out in full public view and the actions were repeatedly questioned.Holding the documents herself, Banerjee addressed the media and explicitly linked the raids to the SIR controversy, alleging that after efforts to “delete voters” did not succeed, the agencies are now attempting to access what she described as the party’s election strategy material.

.

Expressing a sharp reaction, he questioned the role of ED and Union Home Minister Amit Shah. “Is it the duty of the ED or Amit Shah to collect the hard disk of the party and the list of candidates?” he asked. “What will be the result if I raid the BJP party office?”The Enforcement Directorate later moved the Supreme Court, alleging interference during the searches and claiming that Banerjee had entered the raided locations and taken away “key” evidence, including documents and electronic devices – a charge the Chief Minister has denied. old patternThis tendency to involve itself physically in moments of conflict is not new to the 2026 campaign. This reflects a pattern in Mamata Banerjee’s political conduct, which has been visible for decades.In 2021, weeks after Trinamool Congress’ victory in the assembly elections, the CBI arrested four senior party leaders, including two serving ministers, in the Narada sting case. Immediately after the arrest, Banerjee reached the CBI office at Nizam Palace by car and stayed there for about six hours, challenging the action and insisting that if arrests were to be made, they should also be made.

.

Thousands of Trinamool supporters gathered outside and later the CBI, citing law and order concerns, demanded virtual production of the accused.Earlier in 2006, during the Singur land acquisition dispute, Mamata had taken the matter straight to the highway. He went on a 26-day hunger strike protesting the Left Front government’s decision to acquire agricultural land for the Tata Nano project. The protests kept the issue alive in public discussion until it became a central political fault line. In 2008, they also blocked parts of the Durgapur Expressway near the factory site.us vs themIn Bihar, the “vote theft” narrative remained largely a campaign issue. In West Bengal, it has already been introduced and taken forward more clearly. Mamata uses every raid, every notice and every revision of the voter list to strengthen the siege mentality of “us versus them”.Unlike Singur, this phase of mobilization has not depended solely on blockades. It has also focused on neighborhood-level engagement. Across West Bengal, the Trinamool Congress set up “May I Help You” camps, where party workers were instructed to ‘actively work’ to assist voters during the SIR process.Banerjee reiterated that she would never allow any detention camp or deportation of any genuine voter in Bengal. The Chief Minister introduced himself as a “savior”.

.

He has also sought to present this practice as a humanitarian concern. Speaking at the launch of a book he had written on the alleged harassment faced by voters during the SIR hearings, he claimed that at least 110 people had died due to the stress associated with the exercise.“I have written 153 books,” he said. “Nine more books will be published in this book fair… One of these books is a collection of 26 poems on SIR, which will be released in the year 2026.”He used his life as an example to take aim at the Election Commission’s SIR process.She proceeded to use humor and history to highlight the absurdity of the process. She said, “If I write Mamata Banerjee in English and Mamata Bandopadhyay in Bengali, my name will be removed. It is like Rabindranath Tagore and Rabindranath Tagore.” “Someone asked how five children could have the same parents. ‘We two, our two’ is a new concept; earlier it was not like that. We don’t even know when our parents were born.” We were born at home,” he said, before narrating a final anecdote: “Even Atal Bihari Vajpayee once told me that he was not born on December 25.” He made the “vote theft” narrative not about vote theft, but identity theft.Two stages, two reactions In Bihar, allegations of “vote theft” emerged through campaigns, press conferences and post-poll claims, but struggled to sustain themselves as a public action once voting began. In West Bengal, similar concerns have been raised before, repeatedly, and in full public view – through demonstrations, protests, and neighborhood-level engagement ahead of the upcoming elections. In West Bengal, Banerjee has tried to keep controversies over electoral processes out of closed rooms and into public view, and has responded with clear engagement of institutional actions. Whether this strategy ultimately translates into electoral results will be known only when voters cast their votes.