Allan LittleSenior correspondent

BBC

BBCI had been asked to give a key-note speech at a conference at Columbia University’s Journalism School. It was January 2002. Two planes had been flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Centre months earlier and you could still feel how wounded the city felt. You could read it in the faces of New Yorkers you spoke to.

In my speech I made a few opening remarks about what the United States had meant to me. “I was born 15 years after the Second World War,” I said, “in a world America made. The peace and security and increasing prosperity of the Western Europe that I was born into was in large part an American achievement.”

American military might had won the war in the west, I continued. It had stopped the further westward expansion of Soviet power.

I talked briefly about the transformational effect of the Marshall Plan, through which the United States had given Europe the means to rebuild its shattered economies, and to re-establish the institutions of democracy.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesI told the audience, composed mostly of students of journalism, that as a young reporter I had myself witnessed the inspiring culmination of all this in 1989 when I’d stood in Wenceslas Square in Prague.

Back then I’d watched, awestruck, as Czechs and Slovaks demanded an end to Soviet occupation, and to a hated communist dictatorship, so that they too could be part of the community of nations that we called, simply, “the West”, bound together by shared values, at the head of which sat the the United States of America.

I looked up from my notes at the faces of the audience. Near the front of the lecture hall sat a young man. He looked about 20. Tears were running down his face and he was quietly trying to suppress a sob.

At a drinks reception afterwards he approached me. “I’m sorry I lost it in there,” he said. “Your words: right now we are feeling raw and vulnerable. America needs to hear this stuff from its foreign friends.”

In that moment I thought how lucky my generation, and his, had been, to be alive in an era in which the international system was regulated by rules, a world that had turned its back on the unconstrained power of the Great Powers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut it was the words of one of his classmates that come back to me now. He had arrived in New York just a few days before 9/11 from his native Pakistan to study at Columbia. He likened the United States to Imperial Rome.

“If you are lucky enough to live within the walls of the Imperial Citadel, which is to say here in the US, you experience American power as something benign. It protects you and your property. It bestows freedom by upholding the rule of law. It is accountable to the people through democratic institutions.

“But if, like me, you live on the Barbarian fringes of Empire, you experience American power as something quite different. It can do anything to you, with impunity… And you can’t stop it or hold it to account.”

His words made me consider the much heralded rules-based international order from another angle: from the point of view of much of the Global South. And how its benefits have never been universally distributed, something that the Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney reminded an audience at Davos last week.

Reuters

Reuters“We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false,” that young Pakistani student admitted all those years ago.

“That the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient. That trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And we knew that international law applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or victim.”

“Don’t you find it interesting,” he asked, “that the US, the country that came into existence in a revolt against the arbitrary exercise of [British] power is, in our day, the most powerful exponent of arbitrary power?”

A new world order or back to the future?

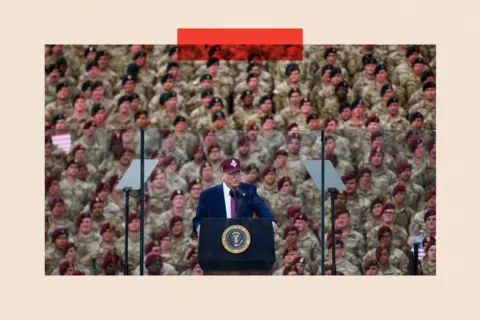

Donald Trump came to Davos last week clearly determined to bend the Europeans to his will over Greenland. He wanted ownership, he said.

He declared that Denmark had only “added one more dog sled” to defend the territory. That speaks volumes to the undisguised contempt with which he and many in his inner circle appear to hold certain European allies.

“I fully share your loathing of European freeloading,” Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth told a WhatsApp group that included Vice President JD Vance last year, adding “PATHETIC”. (He hadn’t realised that the Editor of The Atlantic magazine had apparently been added to the group chat.)

Then President Trump himself told Fox News recently that, during the war in Afghanistan, Nato had sent “some troops” but that they had “stayed a little back, a little off the front lines”.

The comments provoked anger among UK politicians and veterans’ families. The UK prime minister Sir Keir Starmer branded Trump’s remarks “insulting and frankly appalling”.

The UK prime minister spoke to Trump on Saturday, after which the US president used his Truth Social platform to praise UK troops as being “among the greatest of all warriors”.

Carl Court – Pool/Getty Images

Carl Court – Pool/Getty ImagesWe know from the White House’s National Security Strategy, published in December, that in his second term, Trump intends to unshackle the United States from the system of transnational bodies created, in part by Washington, to regulate international affairs.

That document spells out the means by which the United States will put “America First” at the heart of US security strategy by using whatever powers they have, ranging from economic sanctions and trade tariffs to military intervention, to bend smaller and weaker nations into alignment with US interests.

It is a strategy which privileges strength: a return to a world in which the Great Powers carve out spheres of influence.

The danger in this for what Canada’s Prime Minister called “the middle powers” is clear. “If you’re not at the table,” he said, “you’re on the menu”.

Re-interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine

In Davos last week, America’s allies, especially Canada and Europe, were laying to rest what is now commonly called the rules-based intentional order, and in some cases mourning its demise.

But, as the young Pakistani student at Colombia journalism school argued all those years ago, to large parts of the rest of the world it has not seemed, in the last 80 years, that the United States, and on occasions some of its friends, felt restrained by rules.

“After World War Two, we saw, under the so-called rules-based international order multiple interventions by the United States in Latin America,” says Dr Christopher Sabatini, Senior Research Fellow for Latin America at Chatham House.

“It’s not new. There are patterns of intervention that go all the way back to 1823. There’s a term I use for American policymakers who advocate for unilateral US intervention. I call them “backyard-istas” – those who see Latin America as their backyard.”

In 1953, the CIA, assisted by the British Secret Intelligence Services, orchestrated a coup that overthrew the government of Mohammad Mossadeq in Iran. He had wanted to audit the books of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (later part of BP), and when it refused to co-operate, Mossadeq threatened to nationalise it.

For posing a threat to British economic interests, he was overthrown and Britain and the US threw their weight behind the increasingly dictatorial Shah.

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

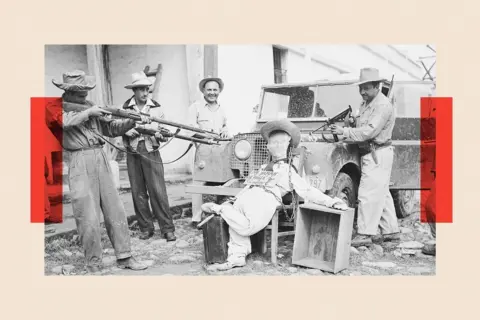

Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesAt the same time, the US was conspiring to overthrow the elected government of Guatemala, which had implemented an ambitious programme of land reform that threatened to harm the profitability of the American United Fruit Company.

Again with active CIA collusion, the left-wing president Jacobo Arbenz was toppled and replaced by a series of US-backed authoritarian rulers.

In 1983 the US invaded the Caribbean island of Grenada, after a Marxist coup. This was a country of which the late Queen, Elizabeth II, was head of state.

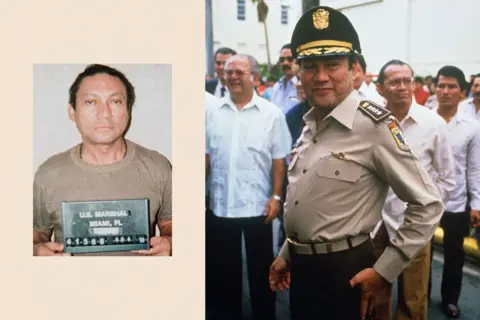

And the US invaded Panama in 1989, and arrested the military leader Manuel Noriega. He spent all but the last few months of his life in prison.

These interventions were all functions of the Monroe Doctrine, first promulgated by President James Monroe in 1823. It asserted America’s right to dominate the Western hemisphere and keep European powers from trying to meddle in the newly independent states of Latin America.

The post-war rules based international order did not deter the US from imposing its will on weaker neighbours.

Getty Images / Corbis

Getty Images / CorbisWhen it was announced by the fifth president of the US, James Monroe, the doctrine that bears his name was widely seen as an expression of US solidarity with its neighbours, a strategy to protect them from attempts by the European great powers to recolonise them: the US, after all, shared with them a set of republican values and a history of anti-colonial struggle.

But the Doctrine quickly became an assertion of Washington’s right to dominate its neighbours and use any means, up to and including military intervention, to bend their policies into alignment with American interests.

President Theodore Roosevelt, in 1904, said it gave the US “international police power” to intervene in countries where there was “wrongdoing”.

So could it be that President Trump’s re-interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine is simply part of a continuum in US foreign policy?

Getty Images

Getty Images“In the Guatemala coup, in 1954, that was entirely owned by the US. They orchestrated the entire takeover of the country,” says Dr Christopher Sabatini.

“The coup on Chile in 1971 [against the left-wing Prime Minister Salvador Allende] wasn’t orchestrated by the CIA but the United States said it would accept a coup.”

During the Cold War, the main motivation for intervention was the perception that Soviet-backed parties were gaining ground domestically, representing Communist advances into the Western hemisphere. In our own day, the perceived enemy is no longer Communism, but drug-trafficking and migration.

That difference aside, President Trump’s reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine “absolutely is ‘back to the future’,” says the historian Jay Sexton, author of The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The other thing that gives Trump’s United States a 19th century feel is his unpredictability, his volatility. Observers could never really predict what the United States would do next.

“We don’t know what the future holds but we do known from even a cursory look at modern history, from 1815 onwards [the end of the Napoleonic wars], that Great Power rivalries are really destabilising. They lead to conflict.”

Cohesion among the allies

American unilateralism may not be new. What is new is that this time, it is America’s friends and allies that find themselves on the receiving end of American power.

Suddenly, Europeans and Canadians are getting a taste of something long familiar to other parts of the world – that arbitrary exercise of US power that the young Pakistani journalism student articulated so clearly to me in the weeks after 9/11.

For the first year of his second term, European leaders used flattery in their approach to Trump. Starmer, for example, had King Charles invite him to make a second state visit to the UK, an honour no other US president in history has been granted.

The Secretary General of Nato Mark Rutte, referred to him, bizarrely, as “daddy”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Trump’s approach to towards Europe brought him clear success.

Previous presidents, including Barack Obama and Joe Biden also believed the European allies were not pulling their weight in Nato and wanted them to spend more on their own security. Only Trump succeeded in making them act: in response to his threats, they agreed to raise their defence spending from around two per cent of GDP to five per cent, something unthinkable even a year ago.

Greenland, however, seems to have been a game-changer. When Trump threatened Danish sovereignty in Greenland, the allies began to cohere around a new-found defiance, and resolved not, this time, to bend.

Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney gave voice to this moment. In his pivotal speech in Davos he said this was a moment of “rupture” with the old rules-based international order – in the new world of Great Power politics, “the middle powers” needed to act together.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is rare, at Davos, for an audience to rise to its feet and award a speaker a standing ovation. But they did it for Carney, and you felt, in that moment, a cohesion forming among the allies.

And in an instant, the threat of tariffs lifted. Trump has gained nothing over Greenland that the US hasn’t already had for decades – the right, with Denmark’s blessing, to build military bases, stage unlimited personnel there, and even to mineral exploitation.

The challenge facing ‘middle powers’ today

There is no doubt that Trump’s America First strategy is popular with his Maga base. They share his view that the free world has been freeloading on American largesse for too long.

And European leaders, in agreeing to increase their defence spending, have accepted that President Trump was right: that the imbalance was no longer fair or sustainable.

Reuters

ReutersIn June 2004 I reported on the celebrations to mark the 60th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy. There were still many living World War Two veterans and thousands of those who had crossed the Chanel 60 years earlier came back to the beaches that day – many of them from the US.

They wanted no talk of the heroism or courage of their youth. We watched them go one by one or in little groups to the cemeteries to find the graves of the young men they’d known and whom they’d left behind in the soil of liberated France.

We watched the allied heads of government pay tribute to those old men. But I found myself thinking not so much of the battles they’d fought and the bravery and sacrifices of their younger selves, but of the peace that they’d gone home to build when the fighting was over.

The world they bequeathed to us was immeasurably better than the world they’d inherited from their parents. For they were born into a world of Great Power rivalries, in which, in Mark Carney’s words, “the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must”.

This was the generation that went home to build the rules-based international order, because they had learned the hard way what a system without rules, without laws, can lead to. They wanted no going back to that.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockThose born in the decades after the war may have made the mistake of believing that the world could never go back to that.

And 24 years ago, as I gave my talk in a New York City still traumatised by 9/11, did I too make the mistake of thinking the post-World War Two order, underpinned, as it was, by American might, was the new permanent normal? I think I did.

For we did not foresee then a world in which trust in traditional sources of news and information would be corroded by a rising cynicism, turbo-charged by social media and, increasingly now, AI.

In any age of economic stagnation and extremes of inequality, popular trust in democratic institutions corrodes. It has been corroding not just in the US but across the western world for decades now. As such Trump may be a symptom, not a cause, of Carney’s “rupture” with the post-World War Two order.

Watching those old men making their way through the Normandy cemeteries was a graphic and poignant reminder: democracy, the rule of law, accountable government are not naturally occurring phenomena; they are not even, historically speaking, normal. They have to be fought for, built, sustained, defended.

And that is the challenge from here facing what Mark Carney called “the middle powers”.

Top picture credit: AFP/Reuters

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. Emma Barnett and John Simpson bring their pick of the most thought-provoking deep reads and analysis, every Saturday. Sign up for the newsletter here