On October 17, the anger of unemployed youth from Telangana erupted on the streets of Hyderabad as they blocked traffic in the central part of the city, raising slogans and demanding postponement of the Group-I examinations scheduled to begin on October 21. They were heading towards the Secretariat – the seat of Telangana administration – while confused motorists watched the scene. Armed with A4-sized print-outs bearing messages of justice, the protesters marched through vehicles, highlighting the gap between the government’s assurances and the harsh reality faced by job seekers.

Among the protesters was 24-year-old K. from Warangal. Nagendra was also included. “The BRS government hired 1,60,000 people. The current Congress government is giving appointment letters to people for jobs whose notification was given by BRS, exams conducted by BRS,” says Nagendra, an Osmania University student who made a reel about the failures of the Congress regime.

Before the protests in October, several protests were held by job aspirants in Ashoknagar and Chikkadapalli area. A few weeks ago, aspirants for teaching jobs had staged a similar protest at the same place, demanding the postponement of the District Selection Committee (DSC) examinations. The protests highlighted discontent among young men and women, for whom state government jobs appear increasingly elusive, almost like a mirage.

The search for jobs has been central to Telangana’s identity and its struggle for statehood. The movement for a separate Telangana took its roots in 1969, when Annabattula Rabindranath started a hunger strike over the appointment policies at the power plant at Kothagudem, which was then newly established. Five decades later, even though that plant’s disused chimney was dismantled for safety, the fight for employment opportunities continues in Telangana, albeit with a new twist.

James, a gracious and soft-spoken young man, makes every visit to Ferrano’s Restaurant in Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad a memorable experience. The 25-year-old, hailing from Manipur’s Lamka Town, about 2,872 km away, secured a job as a server in a newly opened café through the WorkIndia app, a free platform that connects job seekers with employers.

“I used to work in Goa but moved to Hyderabad for better job prospects. My sister also works here,” he shared during the inauguration of the café. James is not alone; Six other persons from Manipur have also found work at Ferrano along with colleagues from West Bengal, Odisha and Telangana.

For many youth like James, Telangana offers diverse opportunities that attract workers from different states across the country. Take the example of Subhan Khan, a young man from Mewat, Haryana, who showed extraordinary courage during the floods that hit Khammam district in September. By driving an earthmover over a bridge amid raging waters, he displayed not only bravery but also skill in rescuing nine stranded people.

a glaring discrepancy

For many, the state, especially the capital Hyderabad, represents a destination of opportunity, where work awaits.

The city has become a magnet for workers from across the country, especially from the North and North-East, who come looking for employment in construction, service sector, IT sector, knowledge work and small businesses. They return to their families after a few days, but Hyderabad remains their work base, promising them livelihood and stability.

However, the strange thing is that millions of local residents are looking for employment. The hub of job search in Telangana is Ashoknagar, a middle-class neighborhood in central Hyderabad that has turned into an end-to-end coaching ecosystem. Here, candidates from all corners of Telangana live, breathe and talk about cracking competitive exams to bag a government job. This business is a serious business, costing up to ₹1.5 lakh per year.

“We spend ₹30,000 on coaching, and monthly expenses, including accommodation and food, come to ₹10,000. Sometimes, we run out of money,” says a candidate who prefers to remain anonymous. “I have been living like this for seven years,” says the candidate for Group I, II and III examination. Tough situations, constant social media buzz, and motivational talks from coaching center mentors foster the belief that the coveted job is just around the corner.

significant difference

According to the ‘India Employment Report’ of the International Labor Organization (ILO), there is a mismatch between the youth population of Telangana and their representation in the job market. While 26.3% of the population is classified as youth, only 39% are part of the workforce. Among males aged 15 to 29, about 9.43% are unemployed, placing the state at 9th position in the national unemployment index.

“Our demand is that the state government should appoint not just 11,062 (through the DSC-2024 system) but 25,000 teachers. They can hire more teachers and pay them less than the prescribed rates. Even if they pay ₹30,000 per month for the next five years, we have no problem with it,” says Pradeep, a candidate campaigning for large-scale recruitment of teachers in Telangana.

“We understand that the government cannot employ two lakh people, but we want them to employ as many people as possible,” says Nagendra.

Stable government jobs remain a priority in Telangana, the state formed a decade ago with the promise of equitable distribution of resources in erstwhile Andhra Pradesh. However, while Telangana was born with the expectation of growth in government jobs, the reality has been more complex. Salary data from Telangana budget shows a steady increase in government employment over the last decade. In 2014–15, when the state was formed, Telangana had 3,74,230 employees. By the next financial year this number dropped slightly to 3,53,250, but by 2024-25 it increased to 4,88,663. This figure is close to the estimate of 4,91,305 jobs in 2021 projected by the CR Biswal-led Pay Revision Commission (PRC).

While the number of employees on the rolls almost matches the sanctioned number, a cursory glance shows how skewed the chart is. A total of 3,23,005 employees are in just three sectors – education, police and health. This validates the demands of job aspirants that the state needs to make more appointments in Group-I, II and III categories.

Limited potential for employment generation

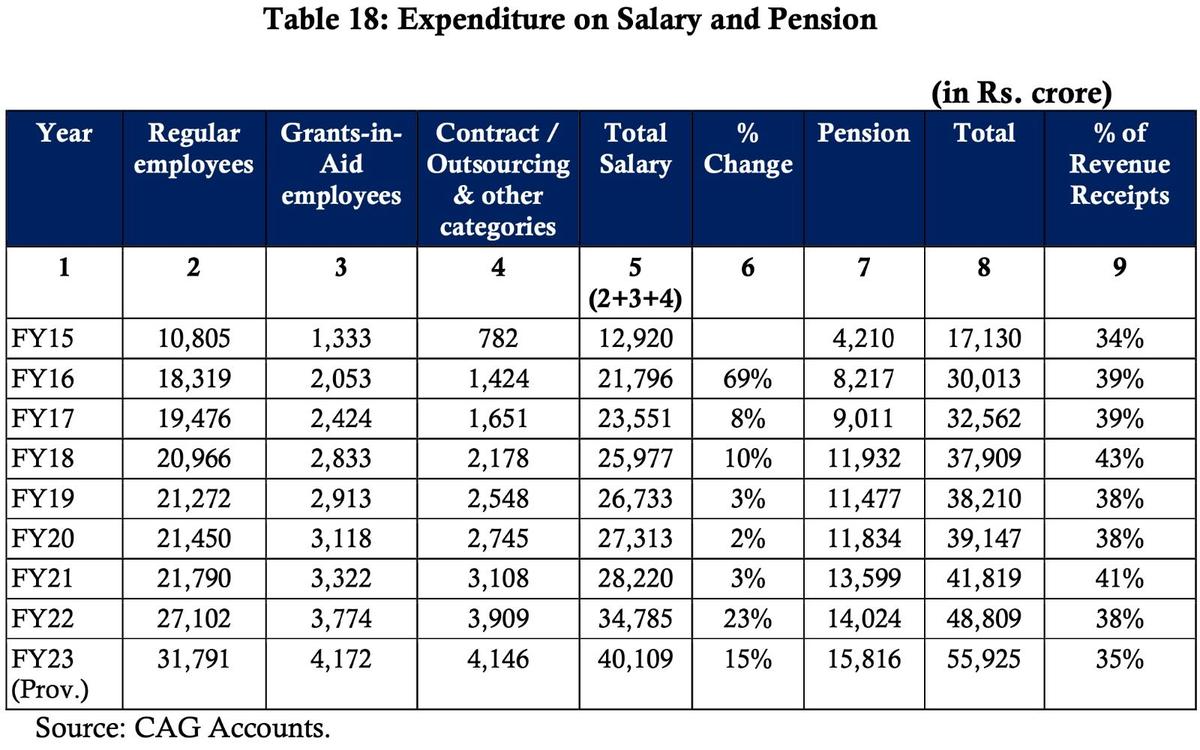

A key indicator of job growth or lack thereof can be seen in the wage bill of the state government. According to Comptroller and Auditor General data, in June 2015-16, just a year after the formation of Telangana, it stood at ₹1,524 crore. By June 2020-21, it declined to ₹1,388 crore.

However, by June 2024-25, the wage bill has more than doubled to ₹3,453.8 crore, reflecting both the recruitment spree and the implementation of the PRC recommendations. Yet, despite this growth, the state’s ability to create jobs and expand its workforce remains limited.

Within weeks of coming to power, the Congress government released a white paper on state finances.

“Overall, expenditure on salaries and pensions has increased almost three times from ₹17,130 crore in FY 2014-15 to ₹48,809 crore in FY 2021-22. “By FY 2021-22, these components account for 38% of the total revenue receipts, which is only expected to increase with the upcoming Pay Revision Commission recommendations, filling of vacancies and payment of dearness allowance arrears,” the document mentions. .

The BRS government aims to make agriculture more profitable through its irrigation projects. “Agriculture and allied sectors in Telangana achieved a year-on-year growth of 11.9% in gross value added (GVA) between 2021-22 and 2022-23,” the socio-economic survey document said. This is an increase of 2.2 percentage points compared to the growth rate of 2021-22. Since the sector employs 45.8% of the state’s population, its economic success is important for improving the standard of living in Telangana.

The state has also promoted a business-friendly environment and created jobs in the private sector. This has led to huge differences in regional income, with Rangareddy district, home to many IT companies, having a per capita income of ₹9,46,862, while neighboring Vikarabad, which has no such industry, has a per capita income of ₹1. As per the latest state budget, 80,241. This inequality has led to significant internal migration, changing the demographic landscape of the state.

“There are no jobs in Mahabubabad. Here, I can earn my living. I sold a piece of land in my village to buy an autorickshaw. I manage to earn ₹30,000 per month. If I put in more effort or spend more time on the road, I can earn more money,” said Mangilal Banoth, 30, who aspired to a police constable job but got a mixed offer six months ago in Upperpally, Hyderabad. Went away. Income neighbourhood, where rent for a one-bedroom house starts from ₹3,000.

“You will find autorickshaws from all the districts of Hyderabad. Earlier they were from three nearby districts. Now, they are from different districts because there are no jobs. if you grow various (rice), the returns are almost the same as the investment. Srinivas Nayak, who belongs to the Banjara community, says, “Nobody from our area of Balanagar, Shadnagar in Mahabubnagar got a job as a police constable despite the ST quota.”

According to the state socio-economic survey, between 2014-15 and 2021-22, IT exports from Telangana experienced a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.67%. Total employment in the IT sector increased from approximately 3.7 lakh to 7.7 lakh during this period. These jobs are largely concentrated in Hyderabad and have a cascading impact on the state’s economy with spin-offs in the service sector and supporting industries.

high levels of unemployment

ILO’s Employment Situation Index, created to understand the job market across the country, has revealed that Telangana is now at the third position after Delhi and Himachal Pradesh. In 2019 it was ranked 16th. But concerns remain as a large section of the youth are unemployed.

Telangana’s labor force participation rate (LFPR) for April-June 2024 was 57.7%, which is below the 60% threshold of other southern states. The LFPR for women was even lower at only 22%. This low participation reflects both the state of the economy and high levels of unemployment.

“If I look for work in my village, Balanagar (Mahboobnagar), I may or may not get a daily wage earning ₹400 to ₹500. But if I come to the city I am assured of work and ₹800 per day. Also, I travel free in the bus, and that’s why we come to Hyderabad for work,” says Lakshmi, who reaches the Langar Hauz Shramik Adda at 8 a.m. every day. This gap between the limited, low-wage jobs in the surrounding rural areas and the abundance of high-paying work in Hyderabad is attracting more people to the city.

The paradox is also visible on social media, where young people share their experiences of how welcoming Hyderabad is to outsiders, with no language barriers, often against the backdrop of the city’s glittering skyline. In contrast, videos of protests – especially near coaching centers in Ashoknagar, Chikkadpally and Dilsukhnagar – highlight the despair of those left behind.

According to government data, Telangana has added 2,518 industries in the last decade, creating 72,908 jobs. These jobs, primarily in the industrial sector, have also created opportunities in supporting and service industries, especially for those seeking short-term gig work. But for young men and women who hoped for stable government jobs when Telangana was formed in 2014, the wait has been long – and continues to be.

published – November 08, 2024 08:17 am IST