On the morning of 2 November, the rhythmic bleating of goats on a hill adjacent to Ulyana village suddenly became silent. Over the next few hours, the village, located in Sawai Madhopur district of Rajasthan, saw the discovery of a dead body, flying axes and improvised low-intensity devices, a protest took place and later in the night, the body of a 12-year-old child was found. Leopard.

The village, which borders the more than 1,500-square-kilometre Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, has often seen Royal Bengal Tigers descending from the forested hills into the low-lying agricultural areas in search of easy prey such as cattle. However, that Saturday, the tiger was reportedly found sitting next to the mutilated body of 50-year-old villager Bharat Lal Meena. Villagers say that one paw of the tiger was on the dead body. Later, he was identified as Chirico or T-86, which was the forest department’s ‘file name’ used for tracking purposes.

According to government data, from 2019 to 2024, five humans have lost their lives in tiger attacks, and more than 2,000 cattle have been killed by tigers in the same period. Although the forest department records the number of tiger-related deaths, there is no record of their killing.

A few days after the incident, there were reports in the media about forest department recordings showing that 25 of Ranthambore’s 75 tigers were “missing”. Officials clarified that 14 tigers were missing for less than a year; 11 for more than a year. An official says there could be several reasons for this: tigers not being captured on surveillance cameras, migration, death due to old age and even poaching. Soon, 10 of the 14 were tracked down. The National Tiger Conservation Authority, which conducts a census of tigers every four years, has asked the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau to look into the matter.

a village mourns

There is mourning in the newly constructed house of Bharat Lal’s family in Ulyana. His wife Prashasti Meena is in a corner of the house, surrounded by female relatives. “There was a lot of commotion; Then someone said that my husband has been attacked by a tiger. What happened next is a blur now,” Prasathi says in a calm voice from beneath the veil that covers her face and neck.

Prasadi, who villagers say fainted seconds after receiving the news, recalls that her husband had taken their goats to graze in the buffer zone between the tiger reserve and their village. Walls have been built around the villages, but they have cracks and many of them require repair.

“My husband used to go out every day around 10.30 am. Even on that day, he had his meal and left with the goats around noon,” says Prasadi, her voice heavy, in sync with the women wailing around her. She was drowning amidst moaning. He never thought that the tiger would take him. “Why didn’t the tiger take the goats and leave him?” She says.

Prashasti Meena, whose husband Bharat Lal Meena was killed along with their son in a tiger attack in Ulyana village in Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur district. , Photo Courtesy: Sabika Syed

Ulyana’s sarpanch Babu Lal, who was at the forefront of the rescue operation, recalls seeing the tiger sitting next to Bharat Lal’s body. “We weren’t sure what his condition was, but his chances of surviving a tiger attack were slim,” he says.

The lower buffer zone, which separates the agricultural land of the village from the lush green tiger belt in the hills, soon saw the growth of a crowd. Babu explains that instinctively, the villagers threw totes (made-made bombs used to break stones), axes, stones and every sharp object they had at the tiger. “I called the forest department and the police, but they did not come immediately and we had to try to save my brother,” he says.

Chirico retreated into the forest and the villagers rushed to Bharat Lal, who had suffered serious injuries. Angry and frustrated by the lack of proactive approach by government agencies, the villagers took his body to the Sawai Madhopur-Kundera Road, about 5 km away.

“More than 1,000 people sat in protest on the road, blocking it for pedestrians. “The mob refused to hand over the body for post-mortem until ₹15 lakh was paid to the family,” says a senior forest department official.

Twenty-one hours later, State Agriculture Minister Kirori Lal Meena met the angry villagers on the road connecting the villages of the district. “The villagers handed over the body and vacated the road only after the minister assured them of compensation,” recalls the officer.

years of anger

This distrust of forest department officials is nothing new, says Dharmendra Khandal, wildlife biologist with Tiger Watch, a non-profit organization involved in wildlife conservation in Ranthambore. “Fateh Singh Rathod (who later became Ranthambore field director) was attacked by villagers of Ulyana in the 1980s. The villagers had broken both his legs. His life was saved only because his driver managed to get between him and the angry mob,” says Khandal.

Rathore, who founded Tiger Watch and is often referred to as India’s ‘Tiger Guru’, was one of the members of the first Project Tiger, launched in 1973 to conserve tigers in the country. Khandal says, “The villagers were angry that they were being displaced by the Rathores to give better structure to the tiger reserve.” He says that today there is a perception among the villagers that the people living in the forest are The reserve is being maintained to attract international tourists at the cost of lives.

The day after Bharat Lal’s death, the forest department formed a search party to look for Chirico. “We could not enter the village as residents were still agitated, and according to humanitarian information we received, the tiger was badly injured after being attacked,” the officer says.

The department sent drones around the forest bordering Ulyana and spotted the tiger’s carcass, about 500 meters away from the spot where villagers had found Bharat Lal’s body. “The Chiricos often preyed on the cattle of nearby villages, but not on any humans. Contrary to what the locals are saying, he was not a man-eater,” he says.

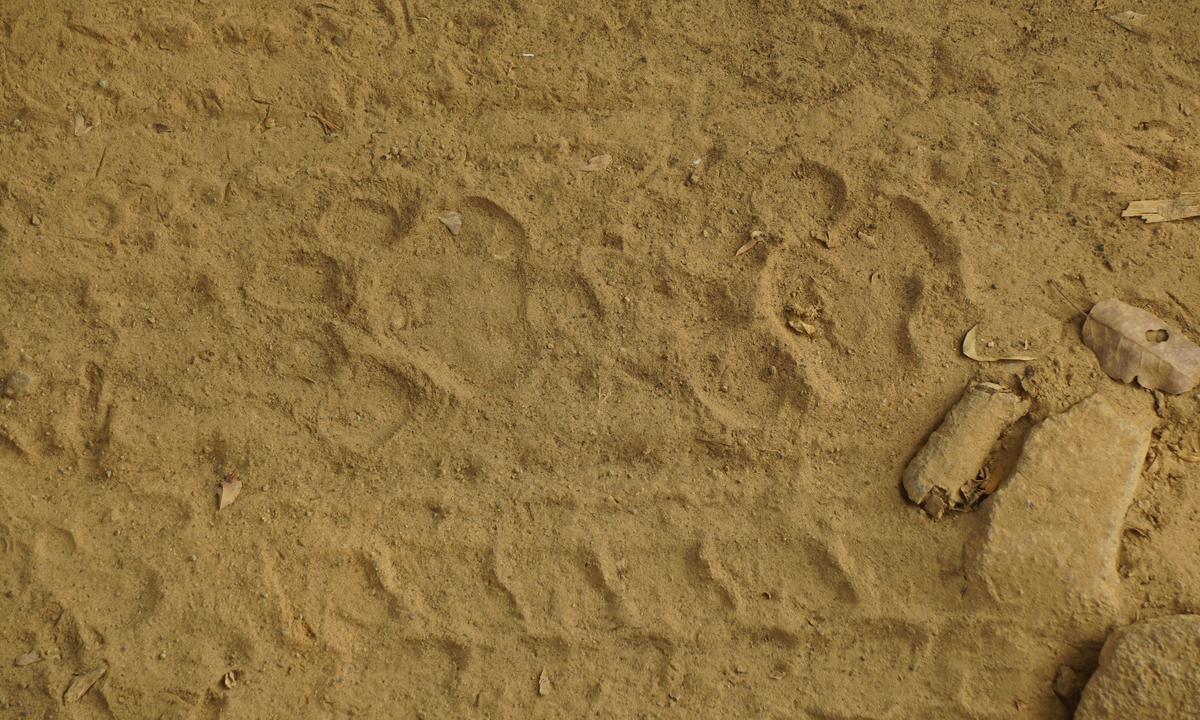

Pugmarks, in the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, are often used to track tiger movements. , Photo Courtesy: Sabika Syed

The official says the tiger had old injuries on its front legs and chest due to a fight for territory with another tiger in the forest. “The post-mortem report showed that those wounds were healing. He died mainly due to injuries caused by sharp objects on his face and back,” he says.

A retired forest department official says that contrary to the perception of villagers, most of the tigers in Ranthambore are not man-eaters. “A man-eating tiger is one that is forced to hunt humans due to the stress of circumstances,” the official says. These circumstances are usually beyond the tiger’s control. “Mostly injured, old tigers resort to becoming man-eaters, but humans are not their natural prey,” he says.

Anup KR, Ranthambore field director, says it is possible that the T-86 wanted to attack the cattle, but since the man was an obstructionist, the tiger attacked him instead.

changing patterns

Despite villagers co-existing with tigers and other wildlife in the area, the increase in man-animal conflict has forced people to change the way they live and work.

In Khawa village in the same district, Bhatti Lal says his brother was killed by a tiger last year when he went out to graze his goats not far from the boundary wall separating the village from the forest. “He was sitting in a hilly area when goats were grazing. The tiger attacked him from behind and dragged him into the forest,” says Bhatti. He further said, since then, herdsmen in the area have started making loud noises while taking cattle for grazing.

Hanuman Meena, another resident of Khawa village, says that most of the villagers are selling their animals at a loss. “An adult goat can be sold for more than ₹10,000, but now fearing for our lives, most of us are selling it for ₹4,000-₹5,000,” says Hanuman. Due to this, they have also been deprived of the livelihood they get from dairy products. Most of the villagers in the area depend on growing wheat, jowar or millet. Some people are employed in the tourism industry.

Animal husbandry communities around Ranthambore National Park are selling their goats and cattle fearing its loss. , Photo Courtesy: Sabika Syed

The news of Bharat Lal’s death also reached nearby villages like Padli. Here in 2019, a woman was attacked by a tiger while defecating in a field. Villagers say that while in Ulyana and Khawa the tigers attacked villagers on the periphery of the forest, in Padli Munni Devi was killed about 6 km from the forest area.

According to their neighbor Rekha Devi, the tiger often roams the guava fields of the village, but this is the first time that it has attacked a human. Rekha says, “At that time, there were no bathrooms in village houses, so women used to use the fields and would leave early in the morning.” She told that the incident happened at 5 in the morning.

The villagers also complain that despite informing the Forest Department several times to increase the height of the boundary walls and maintain them, nothing was done. “At least 30% of our crops are destroyed by wild animals (nilgai, brown bears, leopards). Its cost is not met by the forest department,” says Ramesh Meena, a resident of Padli.

Ramesh says that while the forest department has to pay compensation of ₹5,000 to ₹10,000 for the loss of cattle, in most cases the hassle of traveling more than 15 km to the government office several times over several months is more painful. More than bearing the loss. “Many villagers give up seeking compensation,” he says.

Villagers living in the buffer zone say that the behavior of tigers has changed in the last decade. Lad Devi, 70, of Khawa village, says that tigers and humans have co-existed in this area for a long time. “Tigers used to roam in the fields early in the morning. They kill cattle but never attack humans in this area,” she says.

Lad remembers a day in his childhood when a tiger entered his millet field. “It was a misty morning and when I saw the tiger in the field, I just stood there. She passed me and went to the other end of the field,” she says.

Villagers and a retired forest department official say Ranthambore is full of both tigers and humans. He says that the tigers of this region have historically been migrating towards Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, but for some time this migration has been negligible.

published – November 22, 2024 01:11 am IST