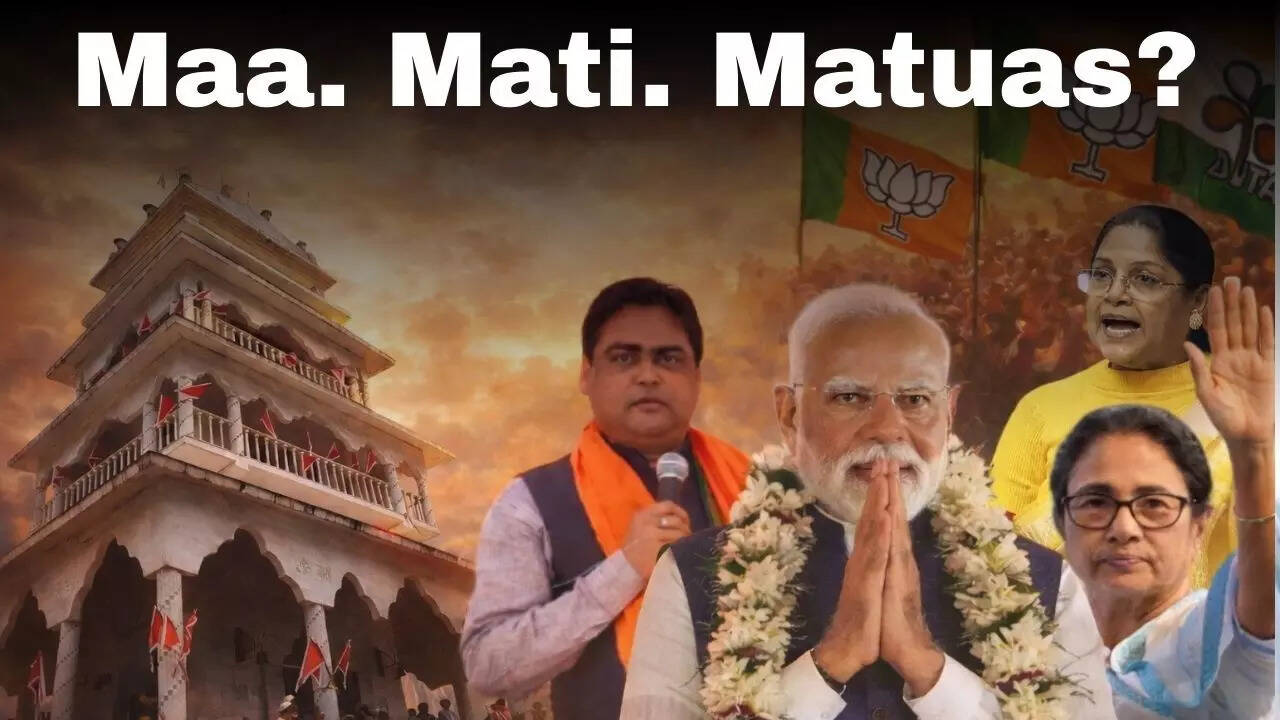

When bad weather forced Prime Minister Narendra Modi to cancel a public meeting in West Bengal’s Ranaghat on December 20, he chose not to let the moment pass quietly. Instead, he sent out a message addressed specifically to the Matua and Namasudra community, acknowledging their decades-long plight and quest to secure a place in the country they now call home.It was a small gesture in form but a telling one in substance.Prime Ministers do not routinely issue targeted messages to caste-based religious communities. That PM Modi did so, even when prevented by the weather, points to a political truth that has been steadily taking shape over the last decade. The Matua–Namasudra community is no longer on the margins of Bengal’s politics. It sits close to the Centre.But can the community deliver what the BJP now seeks in poll-bound Bengal and revive what was once chief minister Mamata Banerjee’s clarion call? Can it set in motion another ‘Poriborton’?

PM Modi post on X

It was a rare direct appeal, naming the community, invoking the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), and framing dignity as a political entitlement rather than a favour. The message raised an obvious question. Why does a missed program with the Matuas merit such emphasis from the Prime Minister of India?The answer lies not in the weather, but in a long and layered history of caste oppression, religious reform, Partition-era displacement, and a steadily growing electoral clout that has turned the Matua–Namasudra community into one of the most closely watched constituents in Bengal’s politics today.“It is not as if the BJP suddenly discovered them. However, with the CAA, the history of the Matuas becomes very interesting. They are, of course, present in certain pockets of Bengal, but they are also scattered in large numbers across the state. With the CAA, the BJP felt that they could vote en masse for the idea of persecuted minorities from Bangladesh getting citizenship, ” Deep Halder, author of “Bengal 2021: An Election Diary”, who extensively covered the last West Bengal assembly polls, told TOI.Halder further said: “The BJP also studied the history of the Matuas, who were a bulwark against Islamisation of the lower castes in East Bengal. During that time, there were a lot of conversions of lower castes into the Islamic fold, and there was also caste discrimination. So they (Matuas), within the Hindu fold, found their own mythology, which gave shelter to many lower-caste Hindus and, in some way, kept them within the Hindu fold. This history also made the community very interesting to the BJP.”

What is CAA

Matua–Namasudras: The question of belonging In the country’s popular discourse, opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) often comes wrapped in the language of constitutional morality, secularism, and “fear of exclusion”. But travel a few kilometres north of Kolkata, into the refugee settlements of North 24 Parganas, and the “popular” framing begins to look very different.For many among the Namasudras in the region, CAA is not an abstract constitutional question. It is a law that finally acknowledges a history they have lived with for generations.Why the Matua-Namasudra community views politics the way it does becomes clearer when one looks beyond electoral arithmetic, beyond BJP versus Trinamool Congress (TMC), and even before the creation of Bangladesh.The Namasudras are not migrants by origin. They are among the indigenous communities of eastern Bengal, once spread across the wetlands and riverbanks of what is now Bangladesh. For centuries, they lived at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, known by the historically stigmatising label “Chandal”. Denied dignity by the caste-driven society, they occupied the margins economically and socially, surviving as peasants, fishermen, and boatmen in Bengal’s agrarian economy.In the late nineteenth century, a quiet revolution began among them. Led by Harichand Thakur, a Namasudra by birth, the Matua movement emerged as a radical break from Brahminical Hinduism. Harichand preached equality, devotion without priestly mediation, and a moral universe in which birth did not determine worth. For the Namasudras, Matua was not just a socio-religious sect, it was an assertion of self-respect.Crucially, this assertion unfolded at a time when conversion to Islam appeared, for some oppressed castes, as a route out of humiliation. However, Harichand Thakur’s teachings offered an alternative. “Thakur was able to offer an independent and alternative space to the Namasudras, away from both Islam and Brahminical Hinduism, but closer to “Dharmic syncreticism”, an admixture of pre-Vedic Kaumadharma, Sahajiya Buddhism and Vaishnavism,” writes Avik Sarkar, an expert on Bengal’s Dalit history, in his article “Subaltern Resistance to Islam and Prospects of Dalit-Muslim Alliance in West Bengal”.

History of Matuas

Harichand’s son, Guruchand Thakur, took this further. He institutionalised education among Namasudras, encouraged political awareness and repeatedly spoke of the community as “Bir Jaati” (Brave race).“The Guruchand Charit is replete with vivid descriptions of the two incidents of communal violence between the Namasudra-Matuas and the Muslims in Eastern Bengal. Guruchand Thakur, the second Sanghadhipati of the Matuas, often addressed Namasudras as “Bir Jaati” (brave race) and called for resisting any attempt to denigrate their collective honour”, Sarkar writes.The Matua movement, by the early twentieth century, had become as much a social force as a religious one.Prolonged plight after PartitionFor the Namasudras, 1947 was not a clean rupture but the beginning of prolonged displacement. Many stayed back in East Pakistan, hoping that a Muslim-majority state would offer them the dignity Hindus had denied. What followed was disillusionment! They found themselves squeezed between religious majoritarianism and economic vulnerability. Communal violence, political instability and the slow erosion of security pushed successive waves of Namasudras across the border.Their migration unfolded over decades, not overnight. The riots of 1950, unrest in the 1960s, and finally the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 forced large numbers to cross into India. They arrived in West Bengal not as migrants seeking opportunity but as refugees fleeing uncertainty. The settlement was harsh. Refugee colonies lacked infrastructure, employment was scarce, and the stigma of being “Bangal outsiders” persisted in the Ghoti-dominated society of West Bengal.Thakurnagar: The Mecca of MatuasOut of partition-led displacement emerged Thakurnagar in North 24 Parganas, which grew from a refugee settlement into the spiritual and organisational centre of the Matua movement after Partition. In the region, religion, memory, and politics are fused. The Matua identity provided continuity to people whose geography had been torn apart. Over time, this shared history translated into political consciousness. The Namasudra–Matua community in the 21st century is among the largest Scheduled Caste groups in West Bengal.

Thakurnagar Matua Mahasangha and Thakur Bari Temple: Credit: Wiki Commons

While there is no official caste-wise count, estimates suggest they form roughly 17 to 18 per cent of the state’s population. Politically, their presence stretches across North and South 24 Parganas, Nadia, Howrah, Cooch Behar, North and South Dinajpur and Malda.Electoral analysts routinely point out that Matua voters influence outcomes in as many as 60-65 assembly seats and are spread across at least six parliamentary constituencies. In a state where margins are often tight, that kind of concentration confers bargaining power.For decades, this power rested largely with the Left and later the Trinamool Congress. Welfare programs, refugee rehabilitation, and grassroots networks kept the community electorally aligned, while the BJP remained peripheral in Bengal until the mid-2010s.Boroma: Matua matriarch & her lineageThe Thakur family of Thakurnagar occupies a symbolic space that cuts across party lines. Binapani Devi, known as Boroma, carried Harichand Thakur’s teachings across India and became the Matua matriarch. After her death in 2019, the state accorded her funeral with full state honour, which reflected the recognition of Matua’s influence even among political rivals.Her grandson, Shantanu Thakur, now BJP MP from Bongaon, represents the intersection of faith and politics in contemporary Bengal. Parties court him not merely for endorsement but for access to a constituency shaped by history rather than ideology alone. At the same time, Boroma’s daughter-in-law, Mamata Bala Thakur, a former Rajya Sabha member, has been associated with the Trinamool Congress, illustrating that the family’s political affiliations cut across party lines.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Matua Community’s ‘Boroma’ Binapani Devi Thakur in Thakurnagar in 2019.

On the “make or break election” potential of the community, Deep Halder says, “The family itself is very divided. There is another side of the family, which is with the Trinamool Congress (TMC). Yes, it is an important voting bloc, but make-or-break, I would not say.”To reduce the Namasudra–Matua community to a vote bank is to miss the point. Their political choices are anchored in a memory of caste humiliation, of religious assertion, of displacement and of delayed recognition. Their power lies not just in numbers but in a shared understanding of what the state has owed them and often failed to deliver. As Bengal’s politics grows more polarised, the Matua–Namasudra community remains a reminder that identity here is not manufactured overnight. It is inherited, negotiated, and, increasingly, exercised at the polling booth.2014: The year of shiftThe shift began after 2014. Identity, citizenship, and belonging entered the political mainstream in a way they had not before. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP won just two of Bengal’s 42 seats. Five years later, in 2019, it won 18. The jump was not accidental. Constituencies with large Matua populations, including Bongaon and Ranaghat, swung decisively.The Citizenship Amendment Act played a role in this consolidation. While the law does not name Namasudras or Matuas, it addresses precisely the condition of non-Muslim refugees from Bangladesh who entered India before 2014. For a community whose migration was born of Partition and persecution, the promise of citizenship was not symbolic. It was existential.That promise, and the delay in its implementation, shaped political expectations. In the 2021 assembly elections, the BJP fell short of forming the government, but it still emerged as the principal opposition with 77 seats, a dramatic rise from its three-seat tally in 2016. Many of these contests were fought tooth and nail in Matua-influenced belts. The 2024 Lok Sabha elections saw the BJP’s numbers in Bengal dip to 12 seats, with the Trinamool Congress winning 29. Yet even then, Matua-heavy constituencies remained competitive, asserting that the community was not locked into permanent allegiance. It votes, increasingly, with a sense of leverage.SIR and the dilemma of citizenshipMore than one lakh voters from the Matua heartland, spread across four assembly constituencies in North 24 Parganas’s Bongaon subdivision, are likely to receive notices for hearings following the publication of draft electoral rolls on December 16.A statement by junior Union minister Shantanu Thakur, hinting at one lakh Matua deletions from voter rolls following SIR, has led to fresh unease in the already anxious Matua belt in Bengal.Speaking at a public meeting at Bagdah’s Garapota, Thakur, also the sabhadhipati of the BJP-backed faction of the All India Matua Mahasangha, said: “If excluding 50 lakh infiltrators means that one lakh people from my community are temporarily deprived of voting, which option is more beneficial?”

BJP’s Shantanu Thakur on SIR

Hitting back, TMC called Thakur’s comment “nothing but a cynical, backstabbing betrayal”.“For years, they (BJP) dangled the mirage of citizenship in front of our Matua brothers and sisters, conning them election after election with honeyed lies, only to stab them in the back the moment the votes were pocketed,” the party said on X. “Now, with the EC reduced to their obedient B-team, BJP has rammed through their Silent Invisible Rigging (SIR) abomination in Bengal, forcing millions of Matuas into a humiliating litmus test of citizenship designed to strip them of their rights and erase their votes,” the party posted.

TMC MP Mamata Bala Thakur-led Matua faction during the hunger strike over SIR

In this context, PM Modi’s assurance that the Matuas “have the right to live in India with dignity thanks to the CAA” could be read as an attempt to reassure the community that the ongoing revision of electoral rolls does not dilute its place or legitimacy in the state.The message appears aimed at separating administrative action from questions of belonging, even as concerns over voter exclusions continue to fuel unease in the Matua heartland.The Bengal battle for 2026On the factors that would probably play on the Matua community’s mind in the 2026 elections, Deep Halder said that “what is happening in Bangladesh explains why they left (East Pakistan) in the first place. Political galvanisation even on this side of the border (West Bengal) would remind them of what is happening on the other side of the border (Bangladesh)”.“The public lynching and burning of a Bengali Hindu man is a very recent memory for the Matuas. There is also a large chunk of Matuas on that side of the border (Bangladesh). I visited their headquarters there, and they are very aware of the developments in Bangladesh today. This would also play on their minds when they vote for either of the political parties.”He said the community may not choose one party solely on the issue of identity, but “identity is a big issue even for Gen Z Matuas”. “They are very aware of their identity and history. Hindus of other persuasions may not be aware of many things, but the Matuas I have met are very aware of their history and the reasons why they did not convert to other faiths, mostly Islam,” Halder told TOI.

Matuas and GenZ

For the Matua–Namasudra community, politics has never been a matter of slogans alone. It has been shaped by memory, by displacement, by the struggle to hold on to dignity across generations, and by the slow negotiation of belonging in a land they have helped build but have often had to justify their place in.Their choices have been pragmatic as much as emotional, guided as much by lived experience as by ideology. That is why their political loyalties have shifted, fractured and reassembled over time, resisting any attempt to be neatly categorised or permanently claimed. As Bengal moves toward another election cycle, the Matua story offers a reminder that electoral behaviour here is rarely divorced from history. Administrative processes, citizenship debates and developments across the border are not abstract issues for this community; they touch upon inherited anxieties and hard-earned assertions.Whether the Matua–Namasudra vote consolidates, fragments or recalibrates itself in 2026 will depend less on promises made from platforms and more on whether the state can convince them that recognition, security and dignity are not provisional, but settled facts of citizenship.