Mexico, Central America and Cuba Correspondent

BBC

BBCAfter the thirtieth consecutive month without rain, the townsfolk of San Francisco de Conchos in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua gather to plead for divine intervention.

On the shores of Lake Toronto, the reservoir behind the state’s most important dam – called La Boquilla, a priest leads local farmers on horseback and their families in prayer, the stony ground beneath their feet once part of the lakebed before the waters receded to today’s critically low levels.

Among those with their heads bowed is Rafael Betance, who has voluntarily monitored La Boquilla for the state water authority for 35 years.

“This should all be underwater,” he says, motioning towards the parched expanse of exposed white rocks.

“The last time the dam was full and caused a tiny overflow was 2017,” Mr Betance recalls. “Since then, it’s decreased year on year.

“We’re currently at 26.52 metres below the high-water mark, less than 14% of its capacity.”

Little wonder the local community is beseeching the heavens for rain. Still, few expect any let up from the crippling drought and sweltering 42C (107.6F) heat.

Now, a long-running dispute with Texas over the scarce resource is threatening to turn ugly.

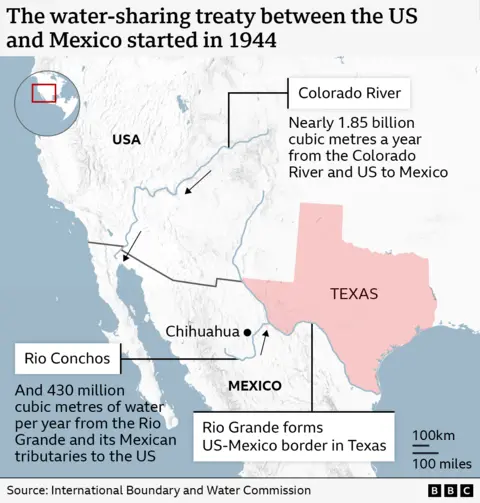

Under the terms of a 1944 water-sharing agreement, Mexico must send 430 million cubic metres of water per year from the Rio Grande to the US.

The water is sent via a system of tributary channels into shared dams owned and operated by the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), which oversees and regulates water-sharing between the two neighbours.

In return, the US sends its own much larger allocation (nearly 1.85 billion cubic metres a year) from the Colorado River to supply the Mexican border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali.

Mexico is in arrears and has failed to keep up with its water deliveries for much of the 21st Century.

Following pressure from Republican lawmakers in Texas, the Trump administration warned Mexico that water could be withheld from the Colorado River unless it fulfils its obligations under the 81-year-old treaty.

In April, on his Truth Social account, US President Donald Trump accused Mexico of “stealing” the water and threatened to keep escalating to “TARIFFS, and maybe even SANCTIONS” until Mexico sends Texas what it owes. Still, he gave no firm deadline by when such retaliation might happen.

For her part, the Mexican President, Claudia Sheinbaum, acknowledged Mexico’s shortfall but struck a more conciliatory tone.

Since then, Mexico has transferred an initial 75 million cubic metres of water to the US via their shared dam, Amistad, located along the border, but that is just a fraction of the roughly 1.5 billion cubic metres of Mexico’s outstanding debt.

Feelings on cross-border water sharing can run dangerously high: in September 2020, two Mexican people were killed in clashes with the National Guard at La Boquilla’s sluice gates as farmers tried to stop the water from being redirected.

Amid the acute drought, the prevailing view in Chihuahua is that “you can’t take from what isn’t there”, says local expert Rafael Betance.

But that doesn’t help Brian Jones to water his crops.

A fourth-generation farmer in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, for the past three years he has only been able to plant half of his farm because he doesn’t have enough irrigation water.

“We’ve been battling Mexico as they’ve not been living up to their part of the deal,” he says. “All we’re asking for is what’s rightfully ours under the treaty, nothing extra.”

Mr Jones also disputes the extent of the problem in Chihuahua. He believes that in October 2022 the state received more than enough water to share, but released “exactly zero” to the US, accusing his neighbours of “hoarding water and using it to grow crops to compete with us”.

Farmers on the Mexican side read the agreement differently. They say it only binds them to send water north when Mexico can satisfy its own needs, and argue that Chihuahua’s ongoing drought means there’s no excess available.

Beyond the water scarcity, there are also arguments over agricultural efficiency.

Walnut trees and alfalfa are two of the main crops in Chihuahua’s Rio Conchos Valley, both of which require a lot of watering – walnut trees need on average 250 litres a day.

Traditionally, Mexican farmers have simply flooded their fields with water from the irrigation channel. Driving around the valley one quickly sees walnut trees sitting in shallow pools, the water flowing in from an open pipe.

The complaint from Texas is obvious: the practice is wasteful and easily avoided with more responsible and sustainable farming methods.

As Jaime Ramirez walks through his walnut groves, the former mayor of San Francisco de Conchos shows me how his modern sprinkler system ensures his walnut trees are properly watered all year round without wasting the precious resource.

“With the sprinklers, we use around 60% less than flooding the fields,” he says. The system also means they can water the trees less frequently, which is particularly useful when the Rio Conchos is too low to allow local irrigation.

Mr Ramirez readily admits, though, that some of his neighbours aren’t so conscientious. As a former local mayor, he urges understanding.

Some haven’t adopted the sprinkler method because of the costs in setting it up, he says. He’s tried to show other farmers that it works out cheaper in the long run, saving on energy and water costs.

But farmers in Texas must also understand that their counterparts in Chihuahua are facing an existential threat, Mr Ramirez insists.

“This is a desert region and the rains haven’t come. If the rain doesn’t come again this year, then next year there simply won’t be any agriculture left. All the available water will have to be conserved as drinking water for human beings,” he warns.

Many in northern Mexico believe the 1944 water-sharing treaty is no longer fit for purpose. Mr Ramirez thinks it may have been adequate for conditions eight decades ago, but it has failed to adapt with the times or properly account for population growth or the ravages of climate change.

Back across the border, Texan farmer Brian Jones says the agreement has stood the test of time and should still be honoured.

“This treaty was signed when my grandfather was farming. It’s been through my grandfather, my father and now me,” he says.

“Now we’re seeing Mexico not comply. It’s very angering to have a farm where I’m only able to plant half the ground because I don’t have irrigation water.”

Trump’s tougher stance has given the local farmers “a pep in our step”, he adds.

Meanwhile, the drought hasn’t just harmed farming in Chihuahua.

With Lake Toronto’s levels so low, Mr Betance says the remaining water in the reservoir is heating up with uncommon speed and creating a potential disaster for the marine life which sustains a once-thriving tourism industry.

The valley’s outlook hasn’t been this dire, Mr Betance says, in the entire time he’s spent carefully recording the lake’s ups and downs. “Praying for rain is all we have left,” he reflects.

Additional reporting by Angélica Casas.